Image 1 of 8

Image 1 of 8

Image 2 of 8

Image 2 of 8

Image 3 of 8

Image 3 of 8

Image 4 of 8

Image 4 of 8

Image 5 of 8

Image 5 of 8

Image 6 of 8

Image 6 of 8

Image 7 of 8

Image 7 of 8

Image 8 of 8

Image 8 of 8

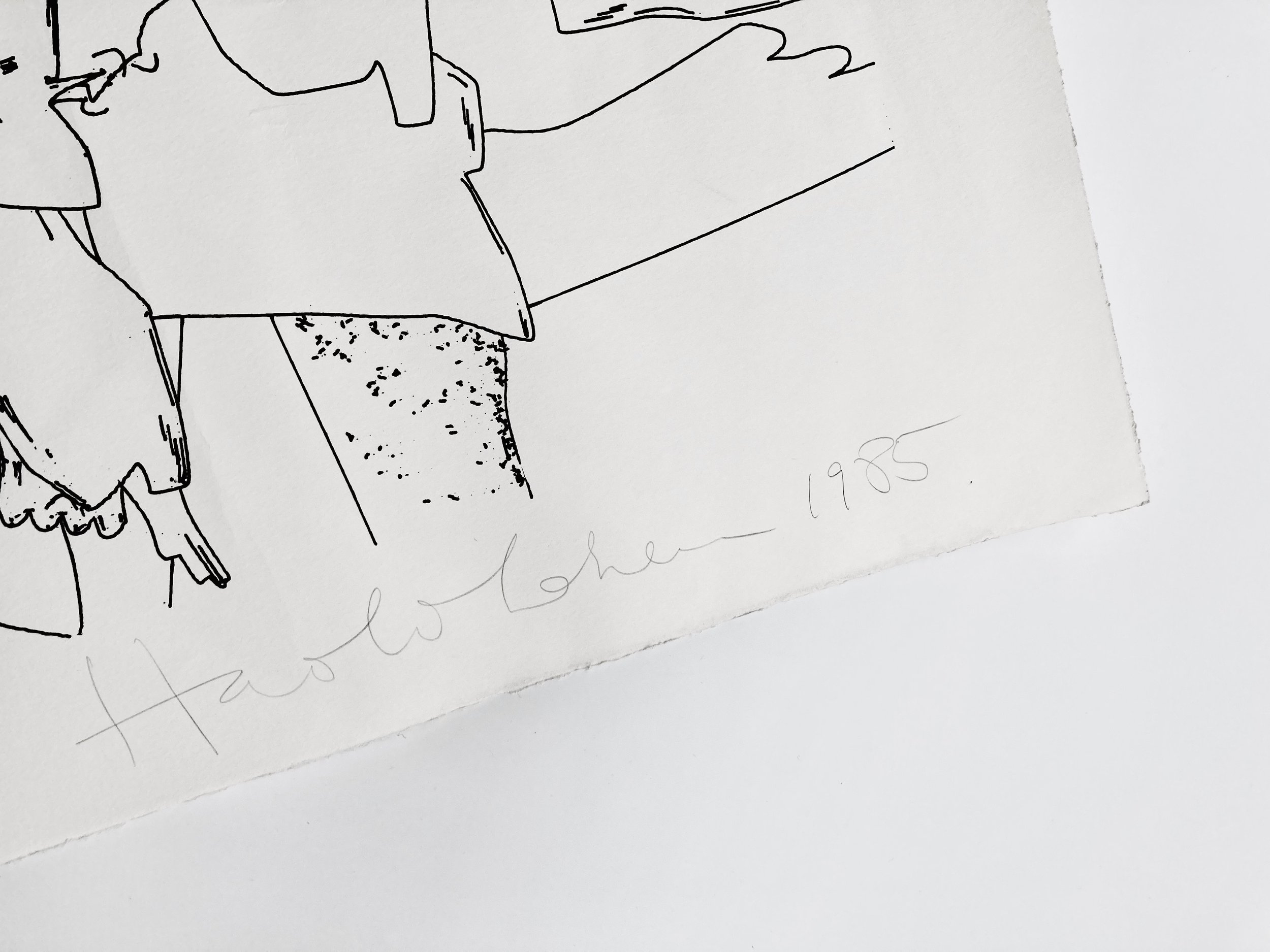

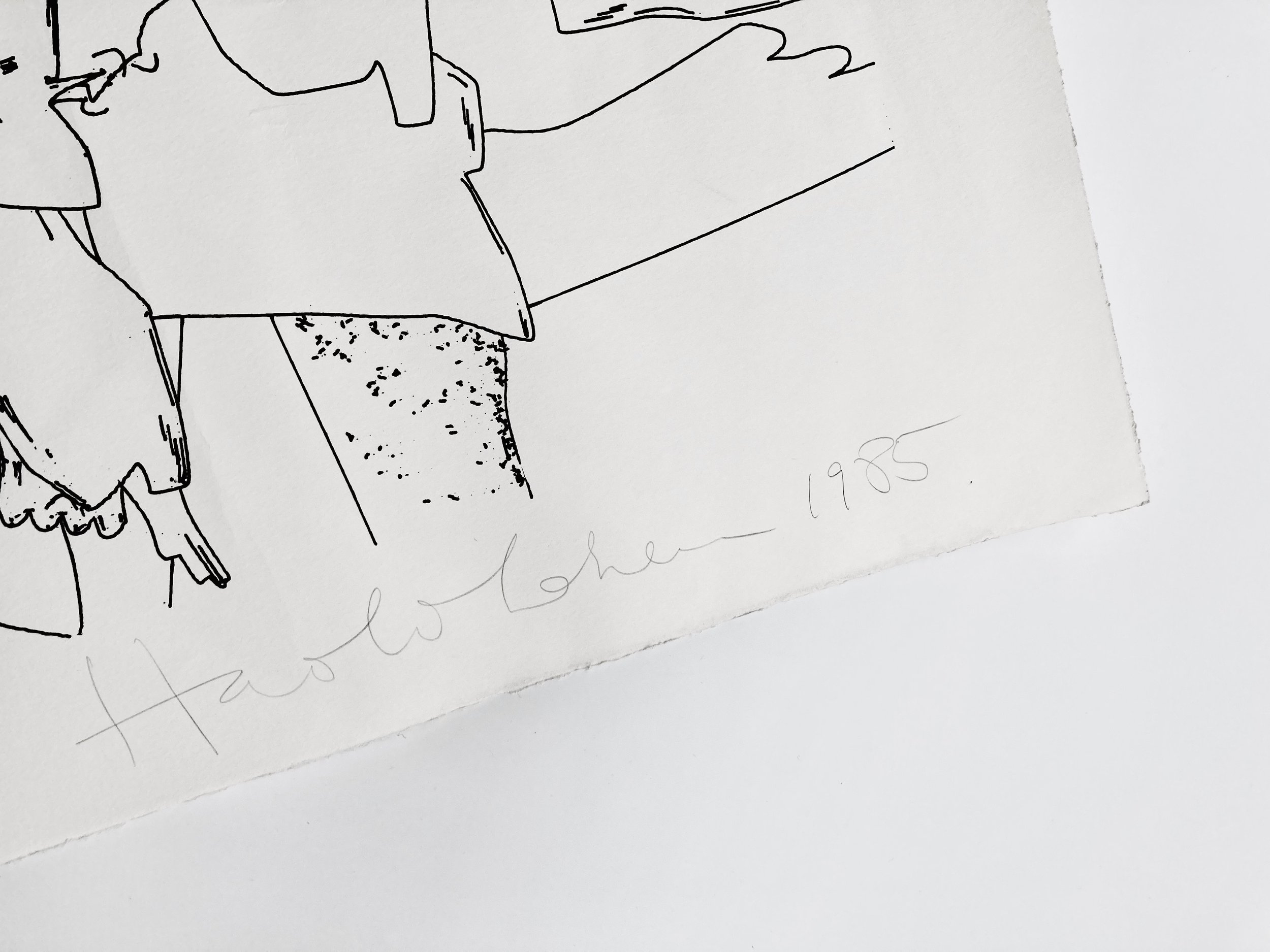

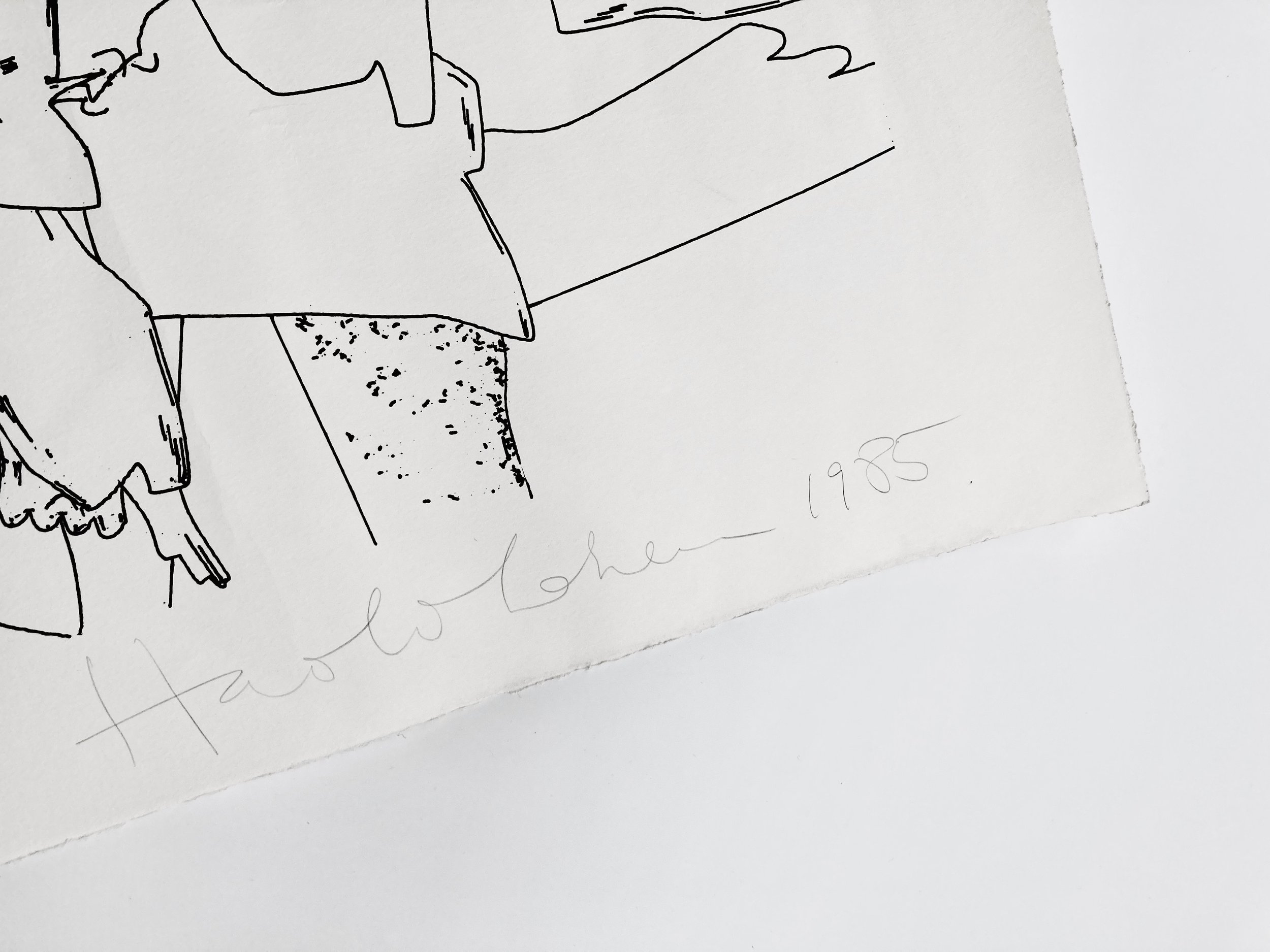

Untitled (1985) | Harold Cohen [AARON]

76 x 56 cm. Unique artwork generated by an AI system (AARON) and produced in real time by a custom robotic drawing apparatus outfitted with a black felt pen. On T. H. Saunders fine paper in light cream stock with four natural deckle edges. Signed and dated in pencil, by Cohen. There is light creasing at center, center left, and the left edge. A small brown spot appears at the top of the work, near the center. That being said, the drawing is crisp and the paper is bright, with no foxing. This is generally a well-preserved example from AARON’s evocative mid-1980s period.

Harold Cohen (1928–2016) was already a successful abstract painter when he first encountered the computer as a visiting professor at the University of California, San Diego, in 1968. Smitten with the machine, Cohen took on a permanent position at UCSD, where he began working on a computer program called AARON. The artist then spent the next five decades—until his death in 2016—continuously developing the system. AARON is now among the most famous AI programs ever created, and it has instigated an entire subfield called computational creativity, where researchers investigate the phenomenon of creativity through computational means.

Like any artist, Cohen’s practice evolved over time, across a series of programming languages (and AI paradigms) and a succession of custom drawing machines, all built by the artist. AARON’s style has changed in turn, proceeding from abstract doodling to more representational forms, and finally back to abstraction (though more expressionistic than the system’s early outputs). While AARON’s initial work is strictly in black, color was introduced in the late 1980s—though Cohen hand-painted some works earlier on, a practice that inspired the legendary First Artificial Intelligence Coloring Book (1984).

For your consideration here is a unique machine drawing signed by Cohen and dated 1985. This piece finds AARON at the outset of a new period that departs from the “rock-art” exhibited in the London / At the Tate (1983) and Arnolfini (1983) series, toward a more ambitious representational system that proceeds from abstract non-visual knowledge about the world. Writing in 1988, Cohen explained this transition:

By 1984 the earlier "rock-art" pictorial paradigm had given way entirely. The pressure to provide real-world knowledge of what AARON's new visual space contained became inescapable and the first of several knowledge-based versions of the program was constructed. […] AARON represents a small part of the flora and the fauna of the world, with a little geology thrown in: a tiny part of the whole of nature. […] Most particularly, its object-specific knowledge contains very little about appearances, and the program's overall strategy rests upon being able to accumulate several different kinds of non-visual knowledge into visually representable forms.

Unlike Cohen’s work produced onsite for specific exhibitions, no series is indicated for this piece. It resembles an example held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, whose catalogue entry cites an origin in Solana Beach, CA—presumably the site of Cohen’s studio at the time. The example offered here exhibits rock-like forms alongside (and behind) highly abstracted biotic forms resembling birds and plants.

To be clear, this is not a print! It is a unique artwork that was conceived by an AI system and physically realized by a custom robotic drawing apparatus. It is an early example by a pioneer of generative art, produced by one of the twentieth century’s most important computer programs. In an era in which tokenized digital images fetch enormous sums, this fiercely nonfungible artifact serves as a relatively inexpensive 1/1—one from the early period of the form, by one of its most important practitioners.

76 x 56 cm. Unique artwork generated by an AI system (AARON) and produced in real time by a custom robotic drawing apparatus outfitted with a black felt pen. On T. H. Saunders fine paper in light cream stock with four natural deckle edges. Signed and dated in pencil, by Cohen. There is light creasing at center, center left, and the left edge. A small brown spot appears at the top of the work, near the center. That being said, the drawing is crisp and the paper is bright, with no foxing. This is generally a well-preserved example from AARON’s evocative mid-1980s period.

Harold Cohen (1928–2016) was already a successful abstract painter when he first encountered the computer as a visiting professor at the University of California, San Diego, in 1968. Smitten with the machine, Cohen took on a permanent position at UCSD, where he began working on a computer program called AARON. The artist then spent the next five decades—until his death in 2016—continuously developing the system. AARON is now among the most famous AI programs ever created, and it has instigated an entire subfield called computational creativity, where researchers investigate the phenomenon of creativity through computational means.

Like any artist, Cohen’s practice evolved over time, across a series of programming languages (and AI paradigms) and a succession of custom drawing machines, all built by the artist. AARON’s style has changed in turn, proceeding from abstract doodling to more representational forms, and finally back to abstraction (though more expressionistic than the system’s early outputs). While AARON’s initial work is strictly in black, color was introduced in the late 1980s—though Cohen hand-painted some works earlier on, a practice that inspired the legendary First Artificial Intelligence Coloring Book (1984).

For your consideration here is a unique machine drawing signed by Cohen and dated 1985. This piece finds AARON at the outset of a new period that departs from the “rock-art” exhibited in the London / At the Tate (1983) and Arnolfini (1983) series, toward a more ambitious representational system that proceeds from abstract non-visual knowledge about the world. Writing in 1988, Cohen explained this transition:

By 1984 the earlier "rock-art" pictorial paradigm had given way entirely. The pressure to provide real-world knowledge of what AARON's new visual space contained became inescapable and the first of several knowledge-based versions of the program was constructed. […] AARON represents a small part of the flora and the fauna of the world, with a little geology thrown in: a tiny part of the whole of nature. […] Most particularly, its object-specific knowledge contains very little about appearances, and the program's overall strategy rests upon being able to accumulate several different kinds of non-visual knowledge into visually representable forms.

Unlike Cohen’s work produced onsite for specific exhibitions, no series is indicated for this piece. It resembles an example held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, whose catalogue entry cites an origin in Solana Beach, CA—presumably the site of Cohen’s studio at the time. The example offered here exhibits rock-like forms alongside (and behind) highly abstracted biotic forms resembling birds and plants.

To be clear, this is not a print! It is a unique artwork that was conceived by an AI system and physically realized by a custom robotic drawing apparatus. It is an early example by a pioneer of generative art, produced by one of the twentieth century’s most important computer programs. In an era in which tokenized digital images fetch enormous sums, this fiercely nonfungible artifact serves as a relatively inexpensive 1/1—one from the early period of the form, by one of its most important practitioners.