Image 1 of 12

Image 1 of 12

Image 2 of 12

Image 2 of 12

Image 3 of 12

Image 3 of 12

Image 4 of 12

Image 4 of 12

Image 5 of 12

Image 5 of 12

Image 6 of 12

Image 6 of 12

Image 7 of 12

Image 7 of 12

Image 8 of 12

Image 8 of 12

Image 9 of 12

Image 9 of 12

Image 10 of 12

Image 10 of 12

Image 11 of 12

Image 11 of 12

Image 12 of 12

Image 12 of 12

Hexapawn: A Game You Play to Lose (1969) | IBM

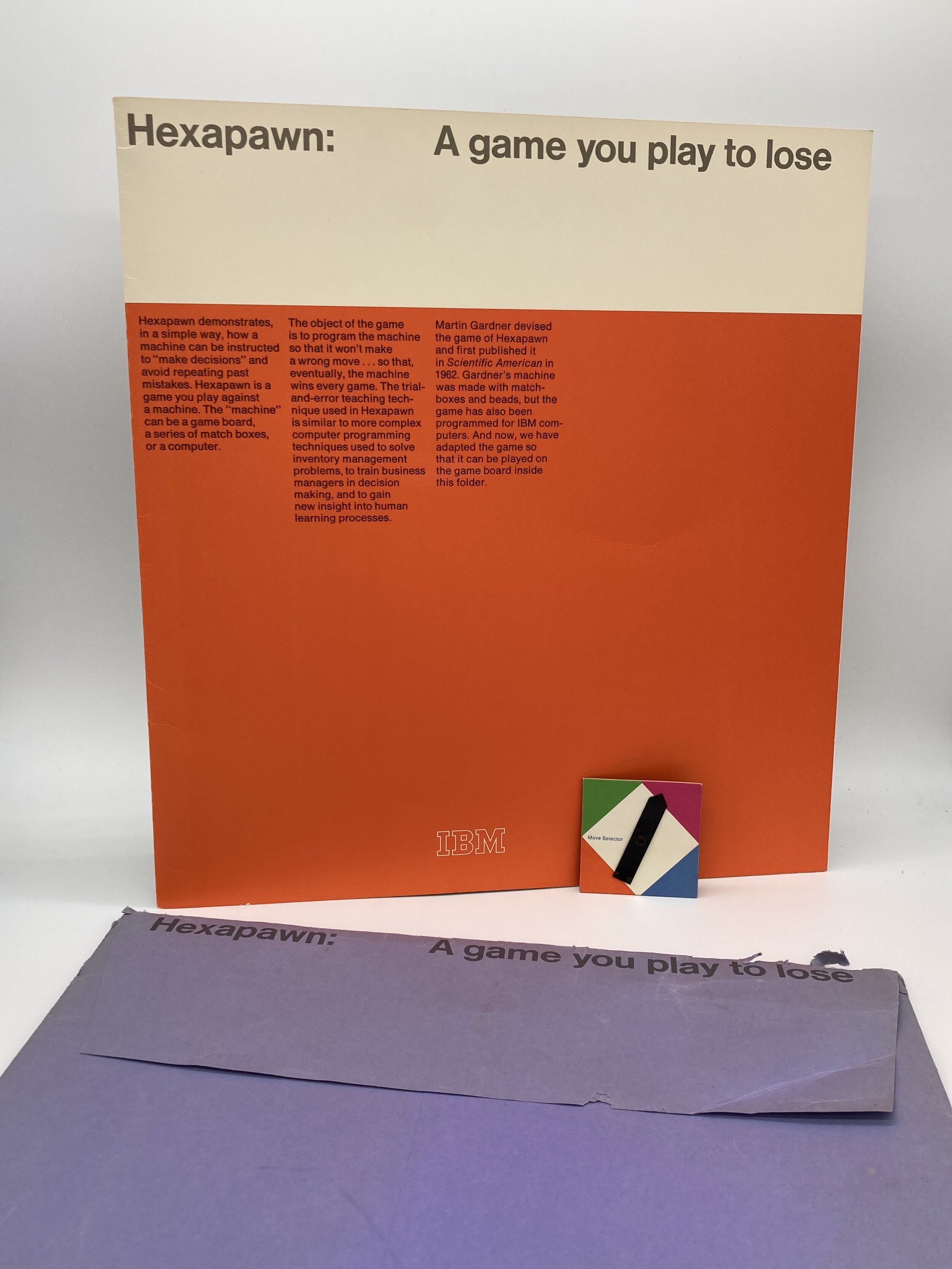

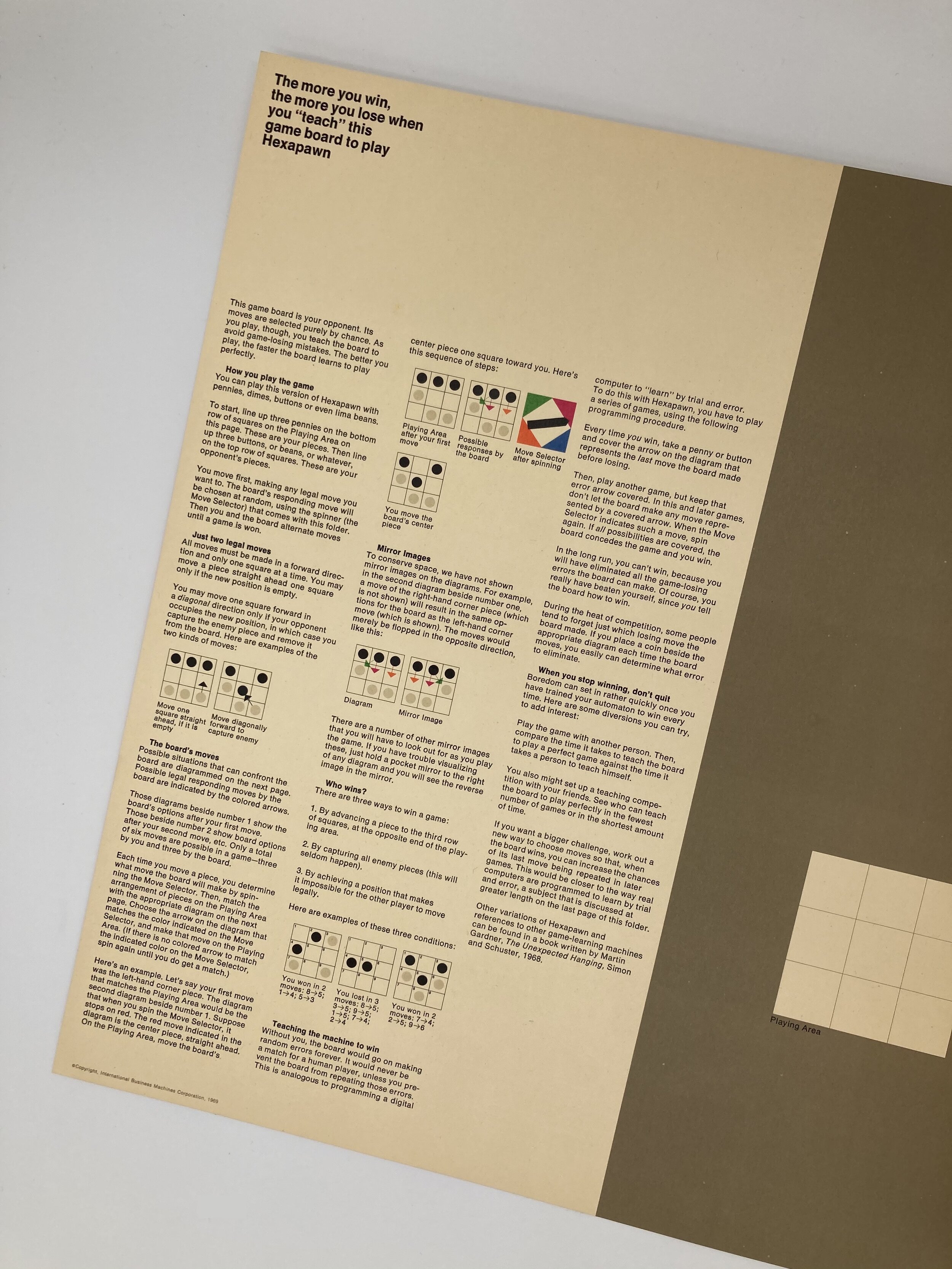

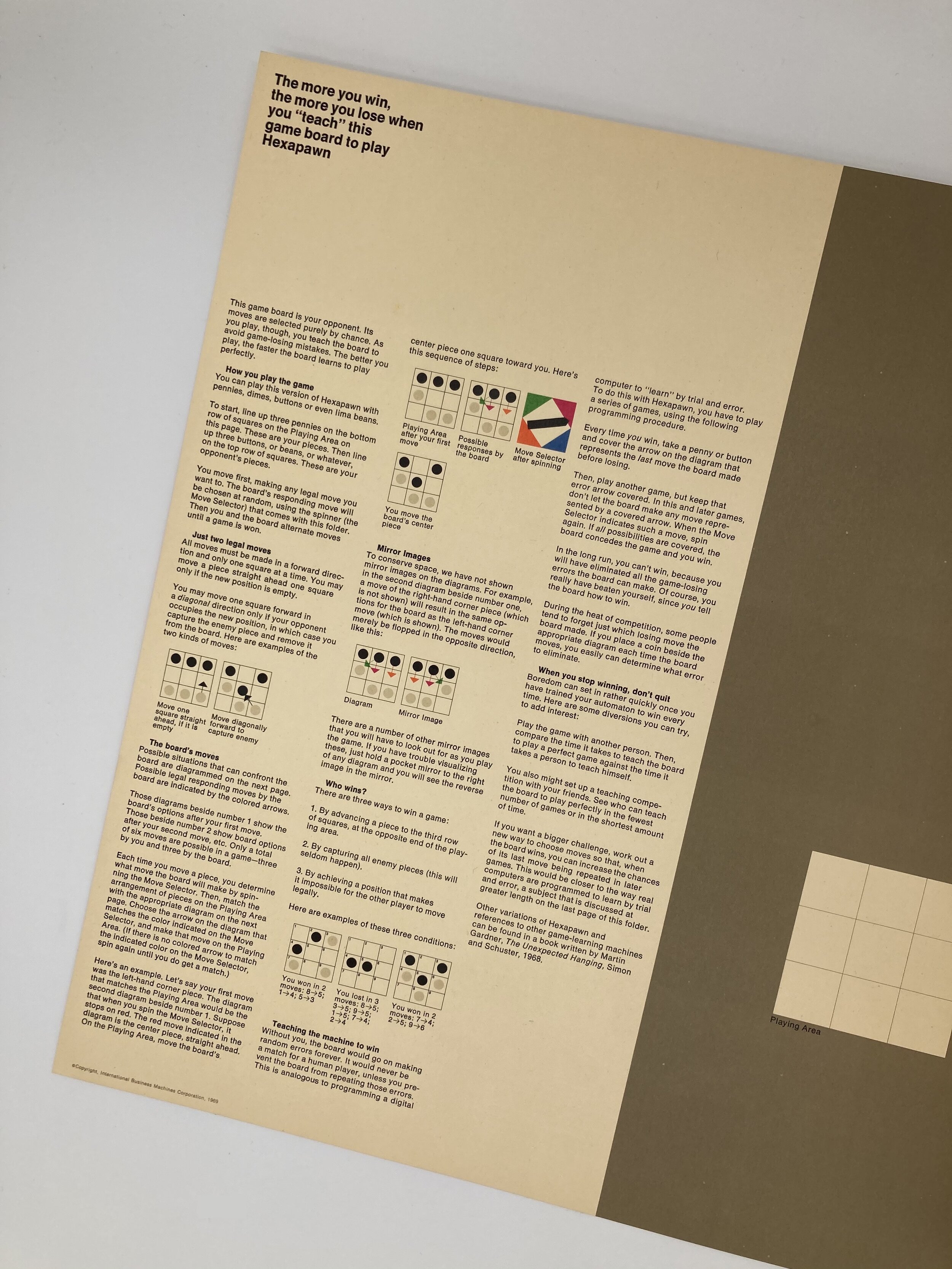

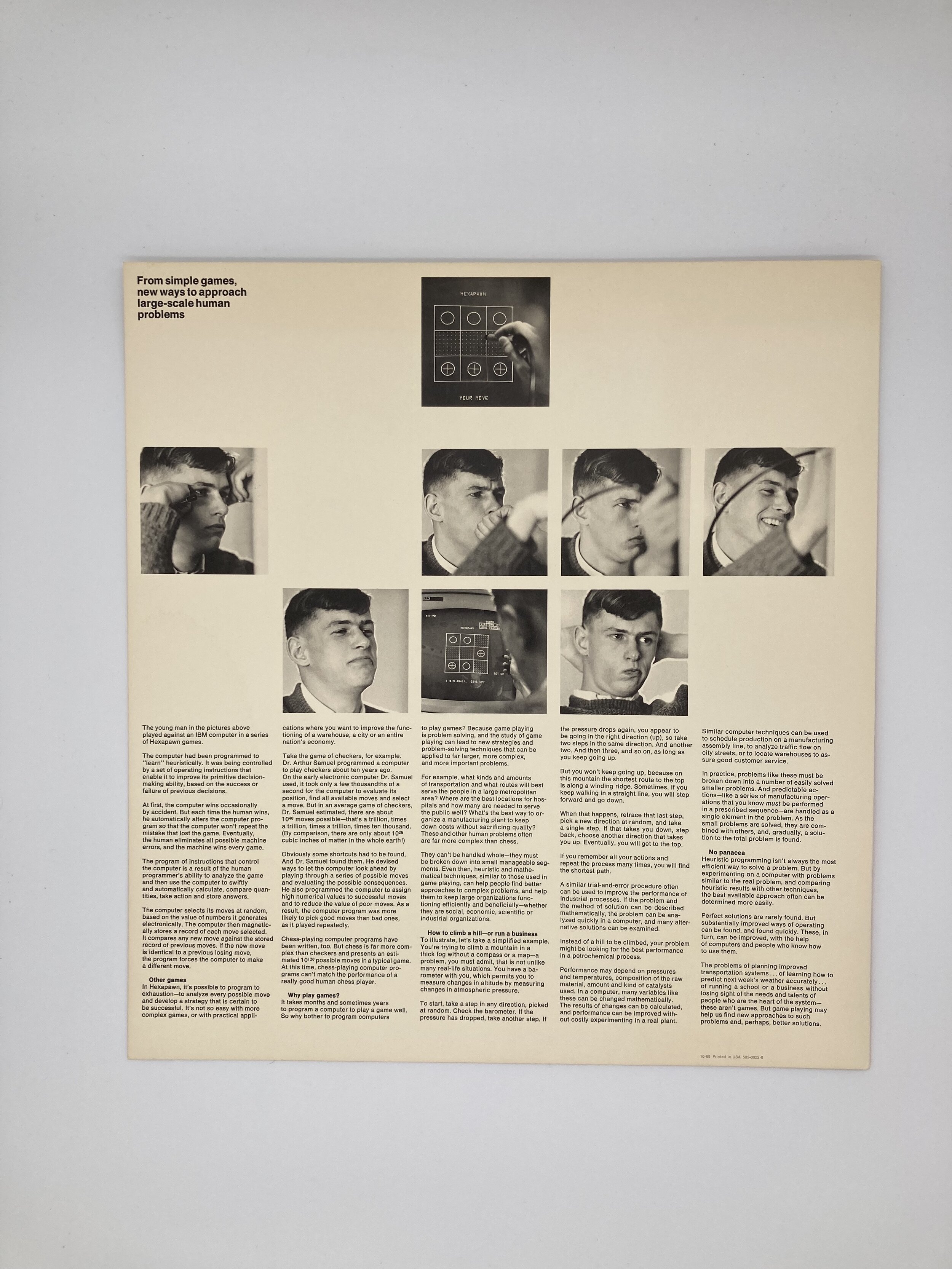

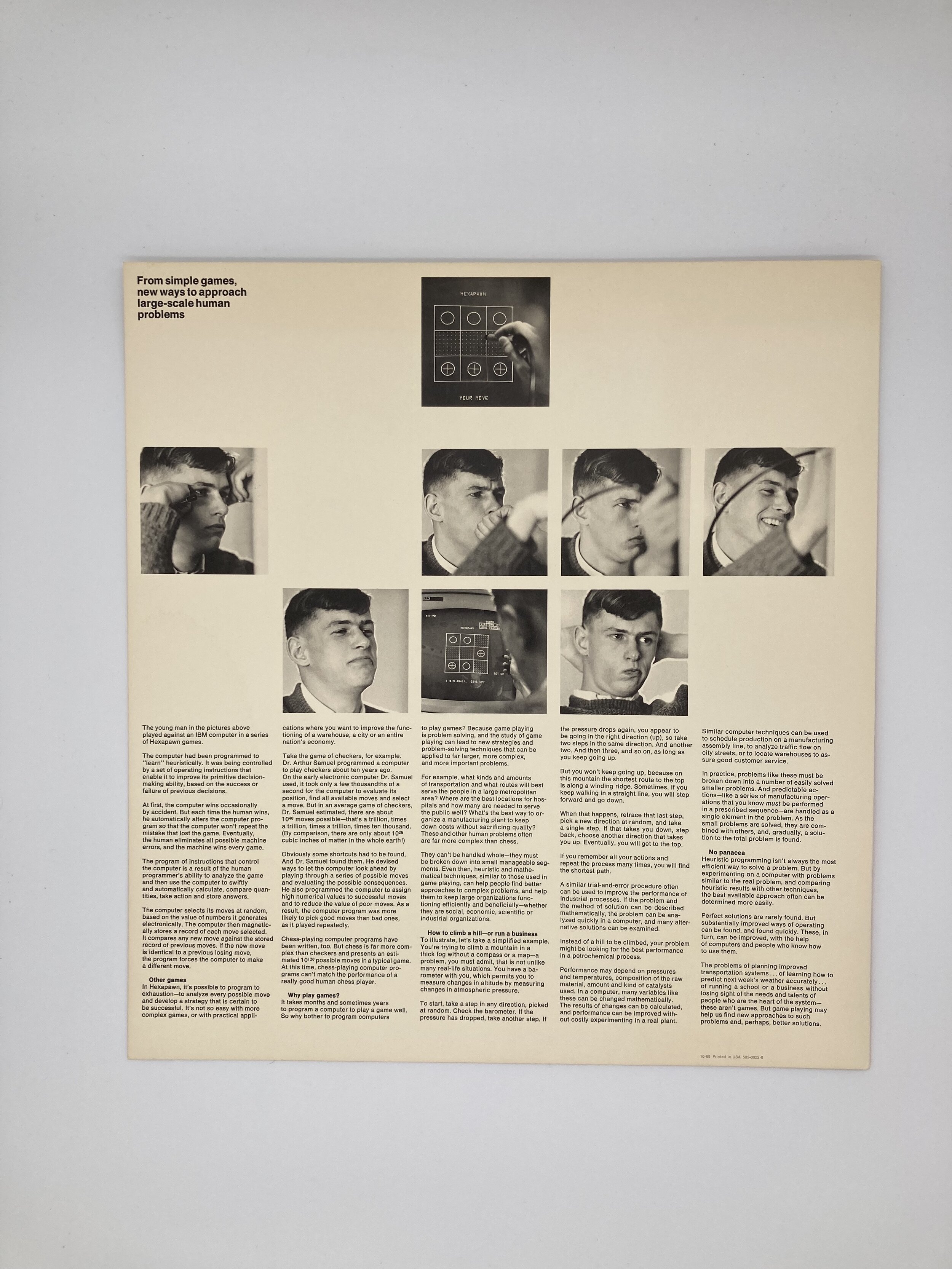

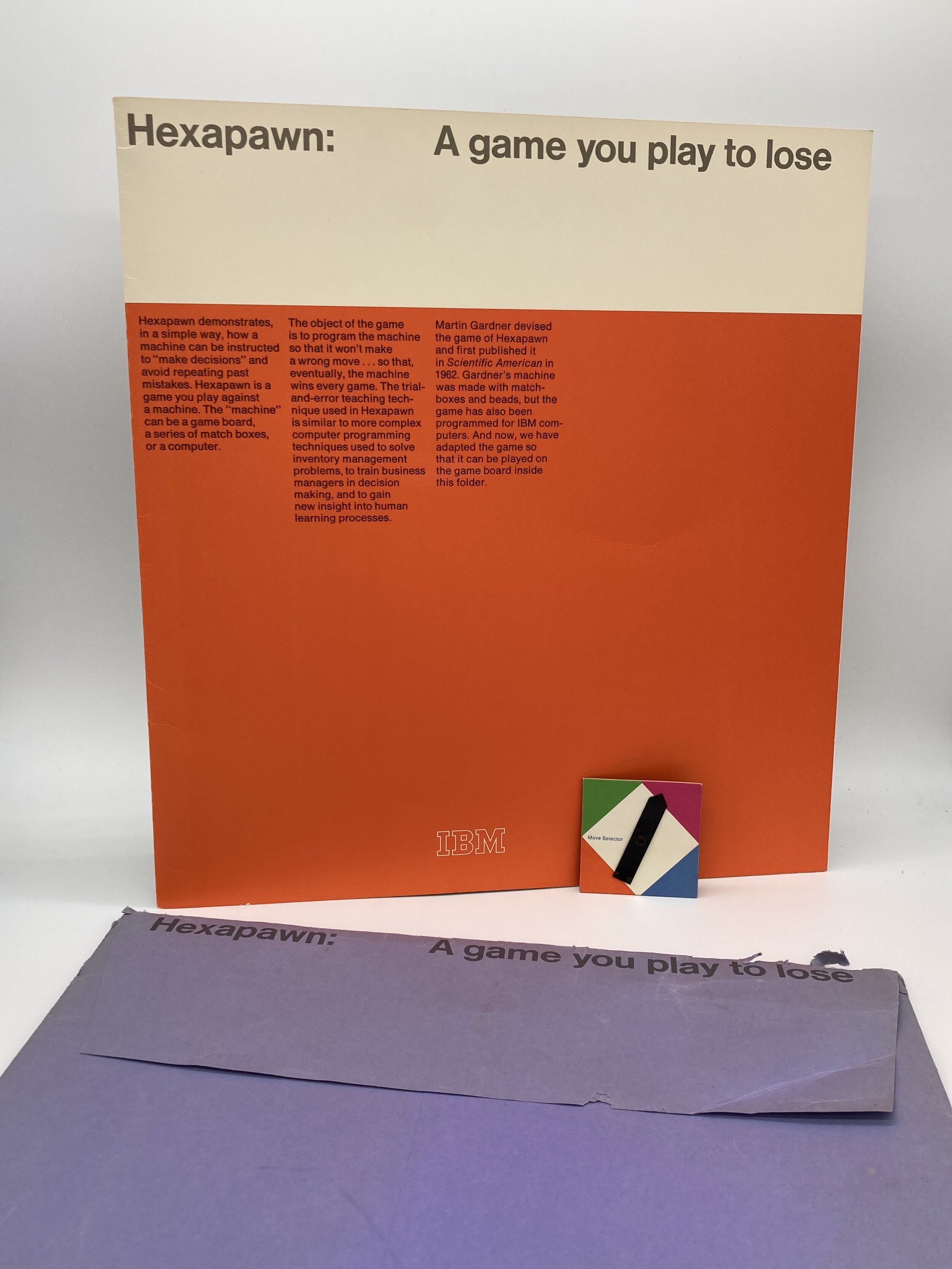

[Hawthorne, N.Y.]: International Business Machines, 1969. Large orange-and-white bifold booklet with printed covers, in original blue printed paper envelope. Includes the sole gamepiece, a “Move Selector” with functional spinner element. 37 x 34cm. [4] pp. The booklet is near fine, with mild creasing to the front cover, and the gamepiece is mint. The envelope is fairly rough, but present and complete.

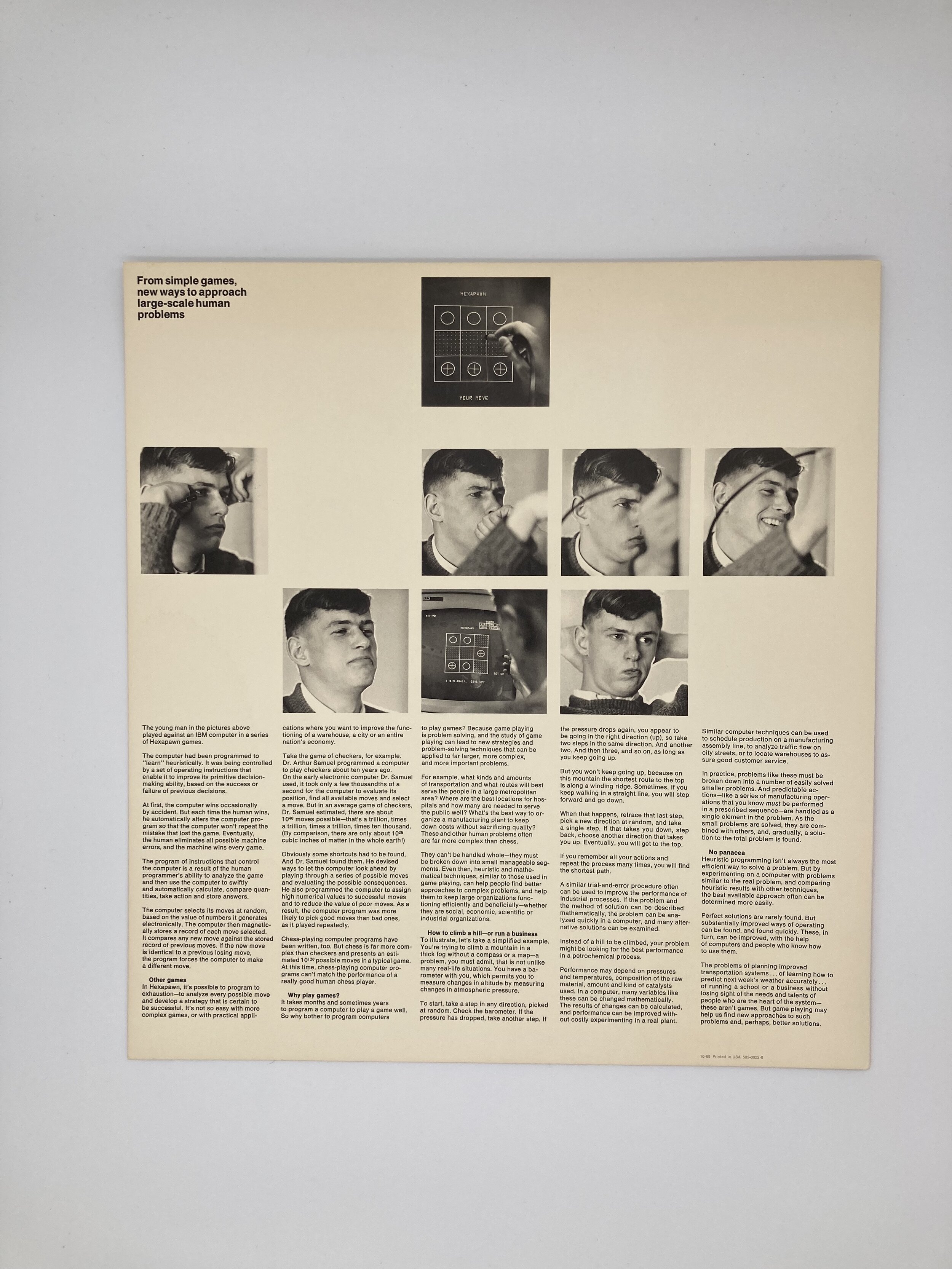

With inspiration from Donald Michie's MENACE, a matchbox-powered tic-tac-toe machine, the polymath Martin Gardner invented Hexapawn in the early 1960s. The game, which was first presented in the March 1962 issue of Scientific American, is a chess variant played on a 3x3 grid with six pawns (hence the name). With perfect play, the player who moves first will always win—i.e., the game is solved.

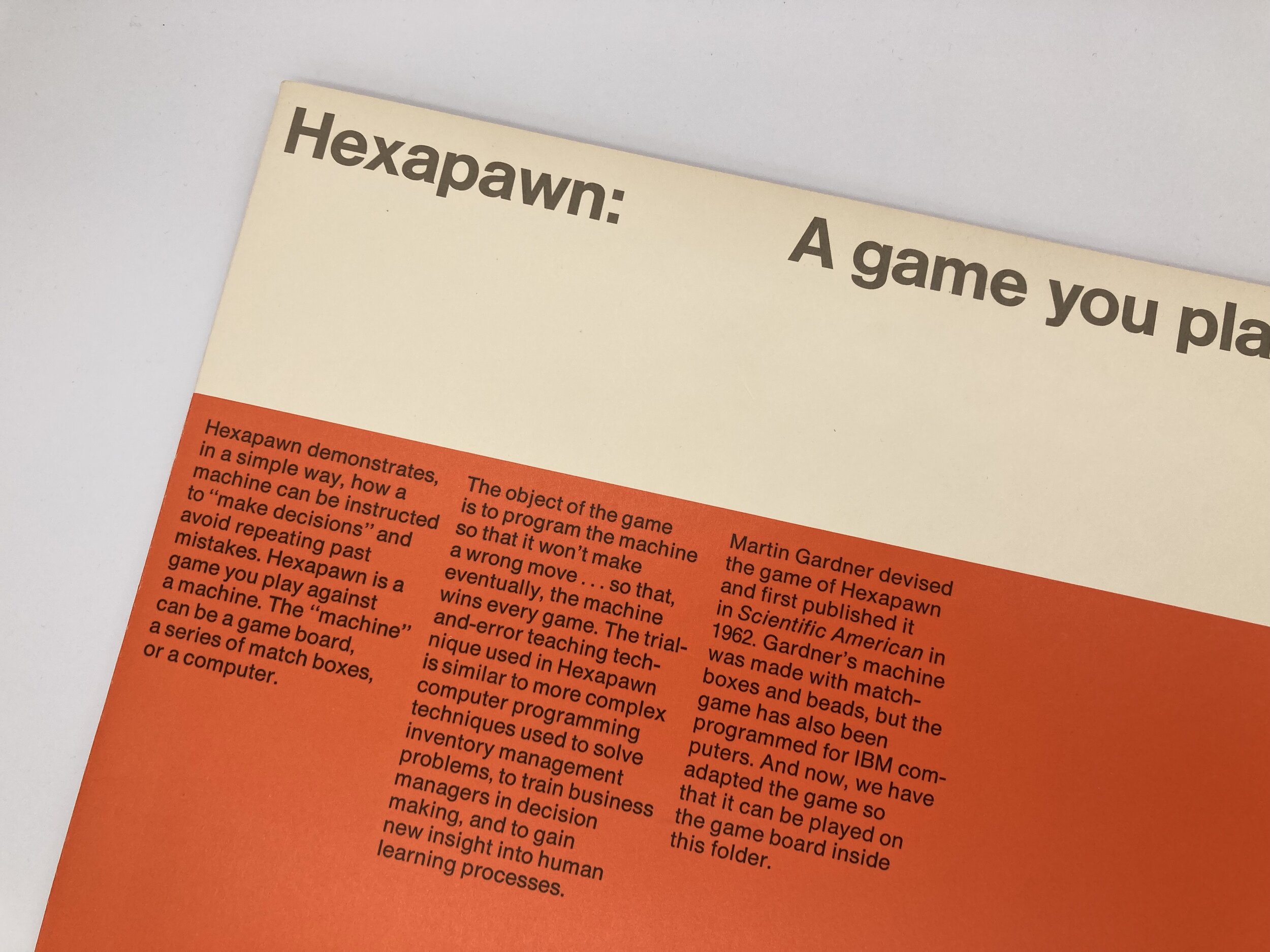

Originally called the Hexapawn Educable Robot, or HER, Gardner’s machine was intended to be constructed using matchboxes containing pieces that control the logic behind the machine’s decisions. What is presented here is a beautifully designed standalone version produced by the world-class industrial designers at mid-century IBM. This booklet was distributed to high schoolers and the general public to promulgate an accessible explanation of the principles of computer programming:

Hexapawn is similar to more complex computer programming techniques used to solve inventory management problems, to train business managers in decision making, and to gain new insight into human learning processes.

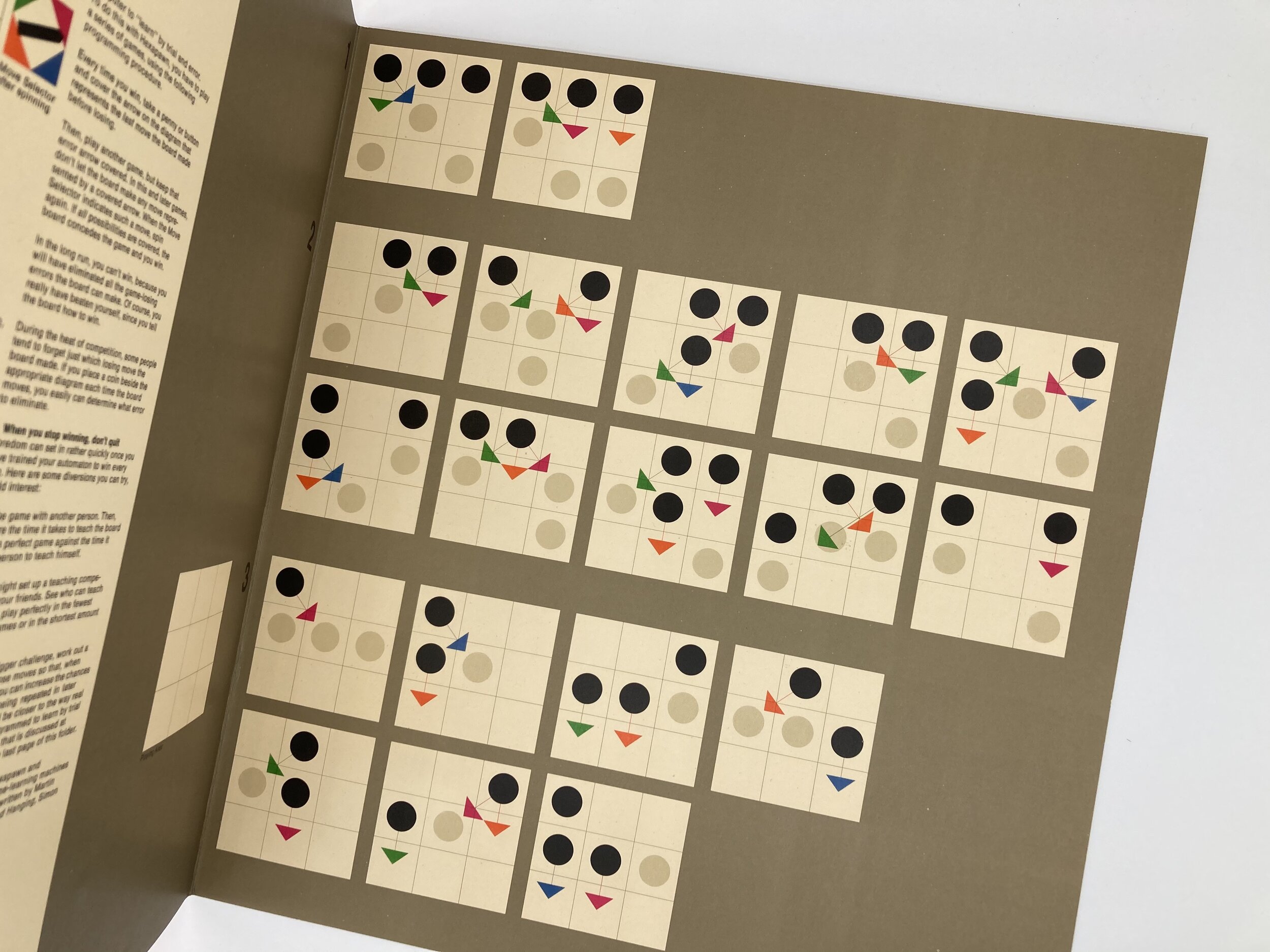

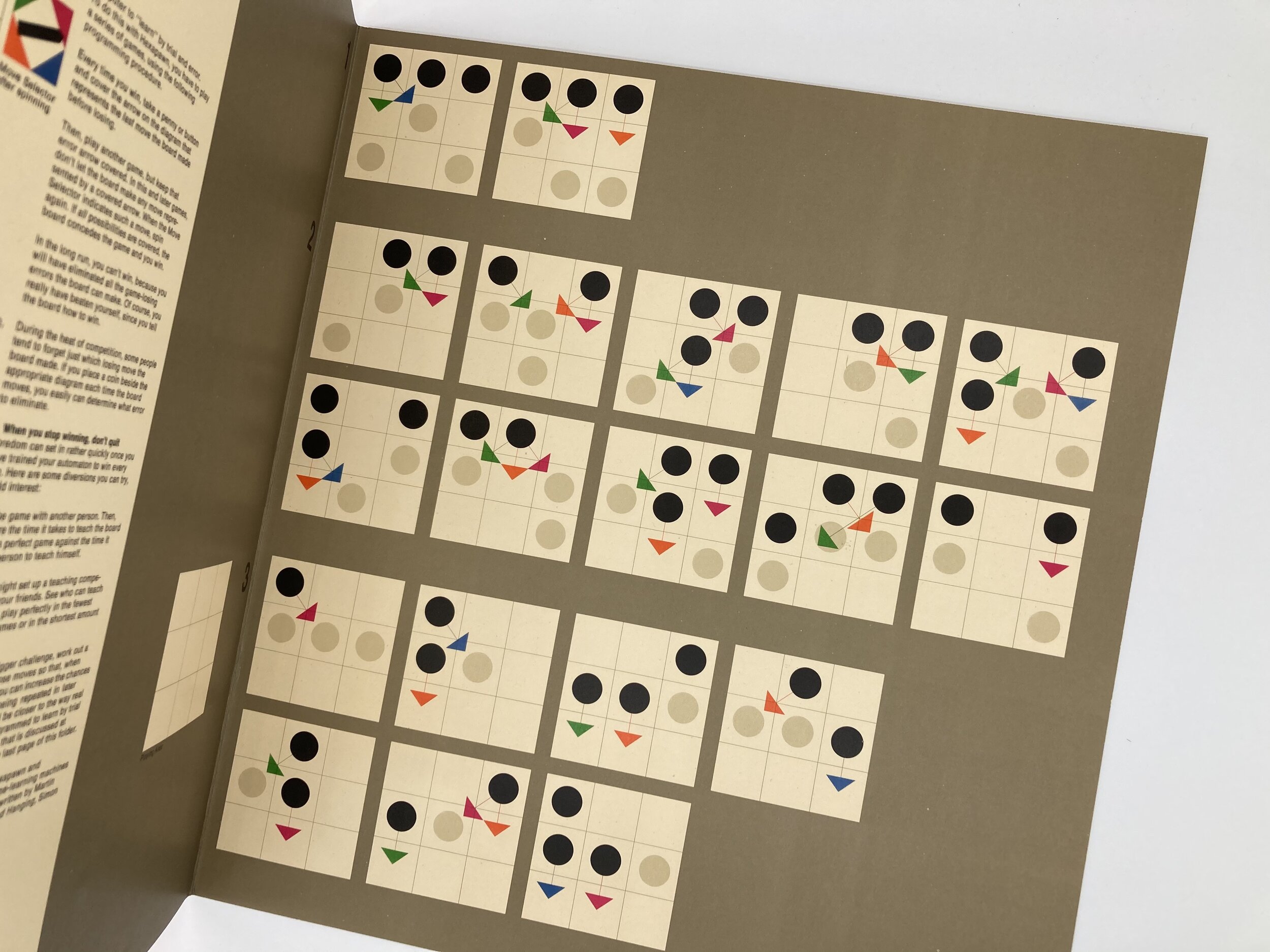

Gardner created Hexapawn to demonstrate the principles of machine learning for heuristic automatic game playing. In particular, it works by a technique called reinforcement learning, which is effectively a regimen of trial and error. As the IBM booklet explains, Hexapawn is played by a human against the game board (or “automaton”), whose decisions are initially made randomly: to make the system’s next move, the player consults the diagram corresponding to the current game state, spins the Move Spinner, and then executes the move whose color is indicated by the spinner. Random play is a poor strategy in Hexapawn, so the human will easily win the first game. Whenever the automaton loses a game, the human places a penny over the portion of the diagram representing the final move played by the automaton. In all subsequent games, such covered moves are eliminated as options for the automaton. Over several games, the automaton will in this manner prune suboptimal moves, eventually “learning” a perfect-play strategy that guarantees victory against the human player.

While gorgeously designed, Hexapawn does not appear to have been widely disseminated and few copies survive today. OCLC locates only a single institutional holding, at East Tennessee State University, though another copy recently appeared in Type Punch Matrix’s first print catalogue (#14). This is a scarce artifact beautifully illustrating the principles behind many of the computational techniques that undergird the AI landscape today.

This item has been sold.

[Hawthorne, N.Y.]: International Business Machines, 1969. Large orange-and-white bifold booklet with printed covers, in original blue printed paper envelope. Includes the sole gamepiece, a “Move Selector” with functional spinner element. 37 x 34cm. [4] pp. The booklet is near fine, with mild creasing to the front cover, and the gamepiece is mint. The envelope is fairly rough, but present and complete.

With inspiration from Donald Michie's MENACE, a matchbox-powered tic-tac-toe machine, the polymath Martin Gardner invented Hexapawn in the early 1960s. The game, which was first presented in the March 1962 issue of Scientific American, is a chess variant played on a 3x3 grid with six pawns (hence the name). With perfect play, the player who moves first will always win—i.e., the game is solved.

Originally called the Hexapawn Educable Robot, or HER, Gardner’s machine was intended to be constructed using matchboxes containing pieces that control the logic behind the machine’s decisions. What is presented here is a beautifully designed standalone version produced by the world-class industrial designers at mid-century IBM. This booklet was distributed to high schoolers and the general public to promulgate an accessible explanation of the principles of computer programming:

Hexapawn is similar to more complex computer programming techniques used to solve inventory management problems, to train business managers in decision making, and to gain new insight into human learning processes.

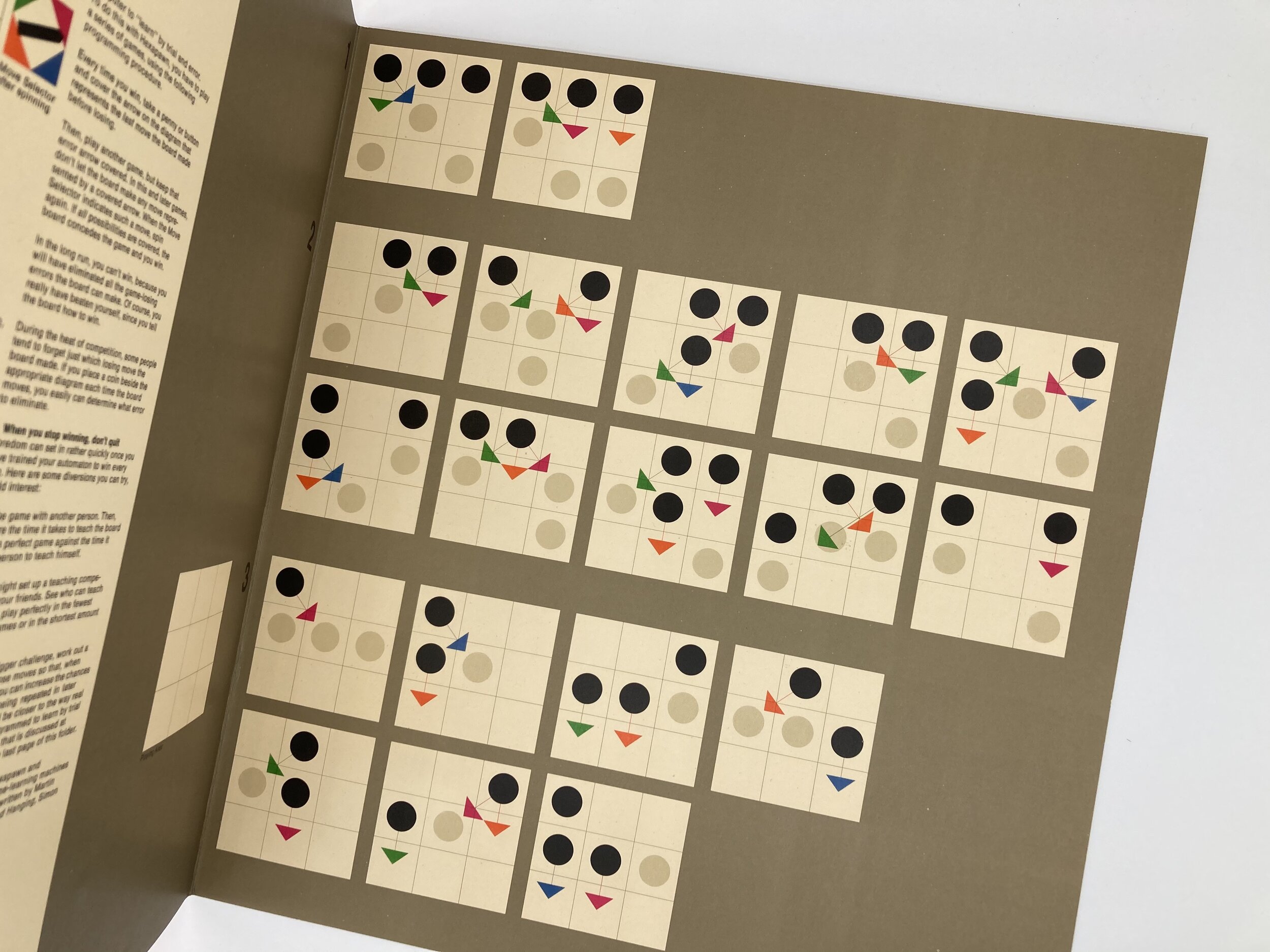

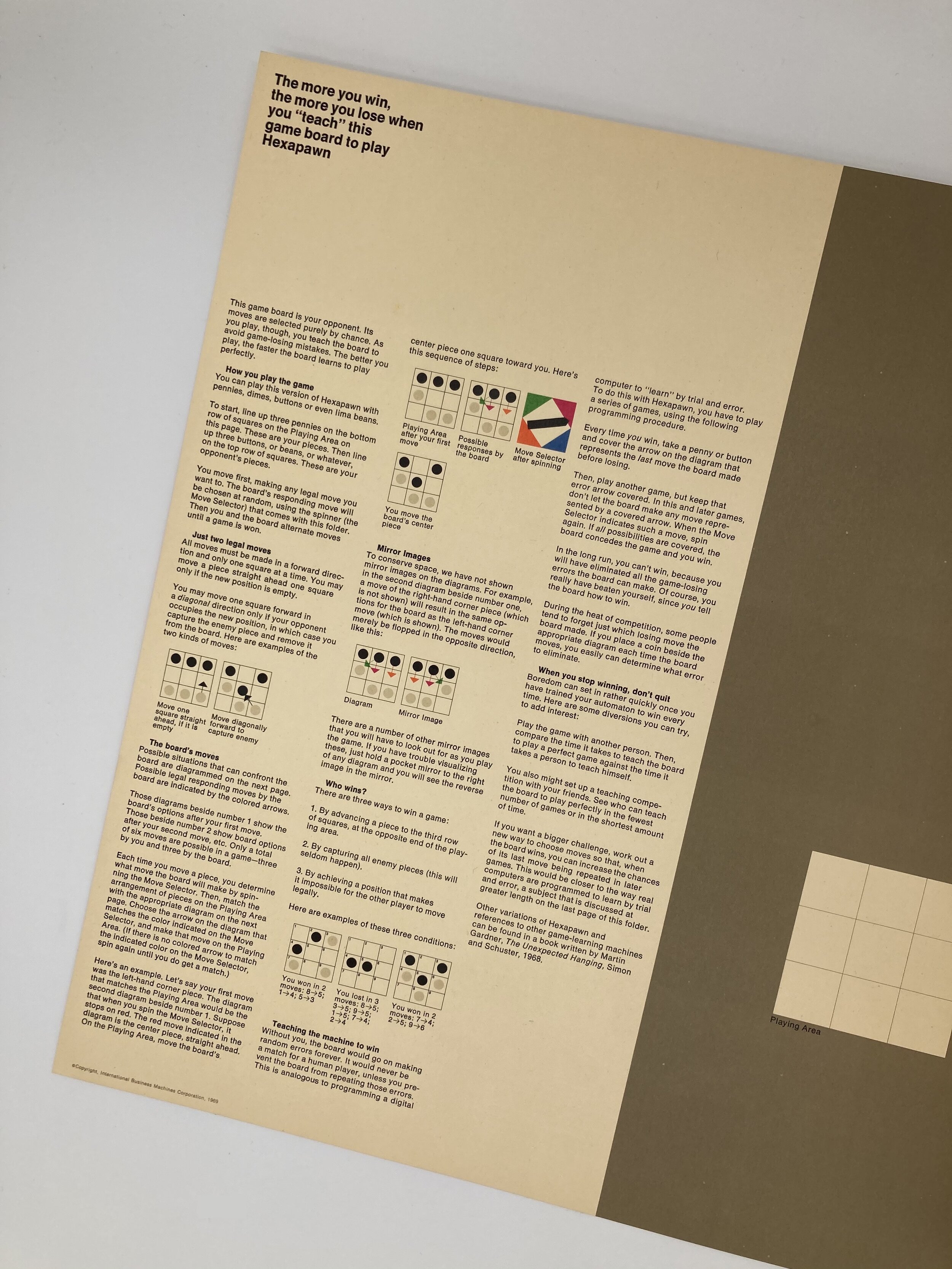

Gardner created Hexapawn to demonstrate the principles of machine learning for heuristic automatic game playing. In particular, it works by a technique called reinforcement learning, which is effectively a regimen of trial and error. As the IBM booklet explains, Hexapawn is played by a human against the game board (or “automaton”), whose decisions are initially made randomly: to make the system’s next move, the player consults the diagram corresponding to the current game state, spins the Move Spinner, and then executes the move whose color is indicated by the spinner. Random play is a poor strategy in Hexapawn, so the human will easily win the first game. Whenever the automaton loses a game, the human places a penny over the portion of the diagram representing the final move played by the automaton. In all subsequent games, such covered moves are eliminated as options for the automaton. Over several games, the automaton will in this manner prune suboptimal moves, eventually “learning” a perfect-play strategy that guarantees victory against the human player.

While gorgeously designed, Hexapawn does not appear to have been widely disseminated and few copies survive today. OCLC locates only a single institutional holding, at East Tennessee State University, though another copy recently appeared in Type Punch Matrix’s first print catalogue (#14). This is a scarce artifact beautifully illustrating the principles behind many of the computational techniques that undergird the AI landscape today.

This item has been sold.

[Hawthorne, N.Y.]: International Business Machines, 1969. Large orange-and-white bifold booklet with printed covers, in original blue printed paper envelope. Includes the sole gamepiece, a “Move Selector” with functional spinner element. 37 x 34cm. [4] pp. The booklet is near fine, with mild creasing to the front cover, and the gamepiece is mint. The envelope is fairly rough, but present and complete.

With inspiration from Donald Michie's MENACE, a matchbox-powered tic-tac-toe machine, the polymath Martin Gardner invented Hexapawn in the early 1960s. The game, which was first presented in the March 1962 issue of Scientific American, is a chess variant played on a 3x3 grid with six pawns (hence the name). With perfect play, the player who moves first will always win—i.e., the game is solved.

Originally called the Hexapawn Educable Robot, or HER, Gardner’s machine was intended to be constructed using matchboxes containing pieces that control the logic behind the machine’s decisions. What is presented here is a beautifully designed standalone version produced by the world-class industrial designers at mid-century IBM. This booklet was distributed to high schoolers and the general public to promulgate an accessible explanation of the principles of computer programming:

Hexapawn is similar to more complex computer programming techniques used to solve inventory management problems, to train business managers in decision making, and to gain new insight into human learning processes.

Gardner created Hexapawn to demonstrate the principles of machine learning for heuristic automatic game playing. In particular, it works by a technique called reinforcement learning, which is effectively a regimen of trial and error. As the IBM booklet explains, Hexapawn is played by a human against the game board (or “automaton”), whose decisions are initially made randomly: to make the system’s next move, the player consults the diagram corresponding to the current game state, spins the Move Spinner, and then executes the move whose color is indicated by the spinner. Random play is a poor strategy in Hexapawn, so the human will easily win the first game. Whenever the automaton loses a game, the human places a penny over the portion of the diagram representing the final move played by the automaton. In all subsequent games, such covered moves are eliminated as options for the automaton. Over several games, the automaton will in this manner prune suboptimal moves, eventually “learning” a perfect-play strategy that guarantees victory against the human player.

While gorgeously designed, Hexapawn does not appear to have been widely disseminated and few copies survive today. OCLC locates only a single institutional holding, at East Tennessee State University, though another copy recently appeared in Type Punch Matrix’s first print catalogue (#14). This is a scarce artifact beautifully illustrating the principles behind many of the computational techniques that undergird the AI landscape today.

This item has been sold.