Image 1 of 19

Image 1 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 19 of 19

Image 19 of 19

Mona by the Numbers (1965) | H. P. Peterson

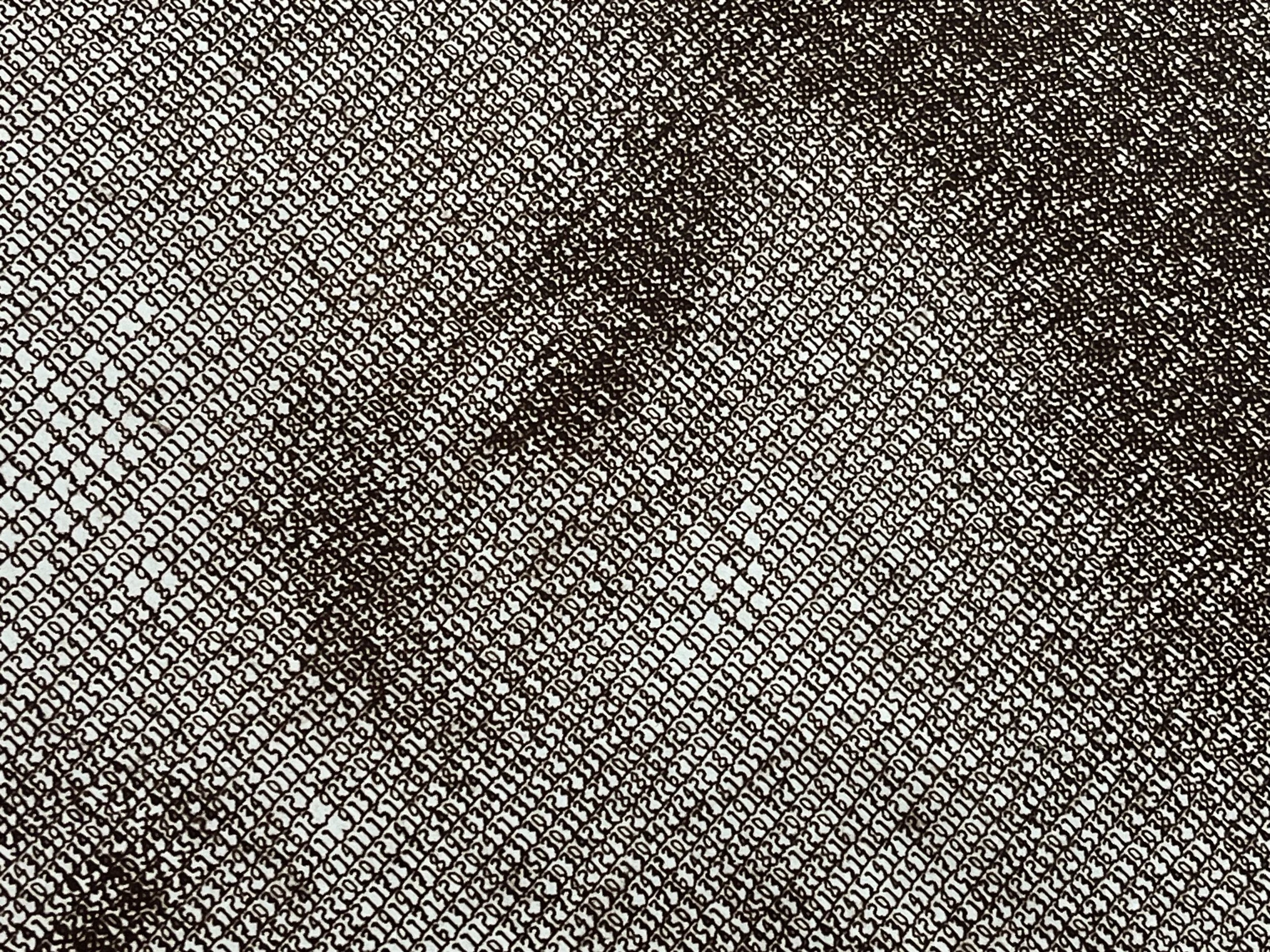

79 x 128 cm. Original diazo sepia print on cream-colored blueline / diazo paper, from a drawing by a CalComp plotter driven by a CDC 3200 computer. The piece is uncut and fully intact, with printed margins indicating the title and artist and his affiliation, along with text along the sides that was printed automatically by the CalComp plotter. What appears to be browning, damage from tape, and holes along the sides are in actuality curious sepia image artifacts that appear to have resulted from a chemical reaction in the diazo paper. Relative to other extant examples, this one shows only minor fading to the image, indicating that it has been shielded from light for its sixty years of existence. This copy appears to have been rolled up for many years, and it is free from creasing. In total, this is an uncut and uncreased copy of a scarce piece, with condition issues in the margins and only minor fading to the image itself.

Among the earliest works of computer art, Mona by the Numbers (1965) was easily the most famous in its own time. Indeed, this masterpiece is arguably the iconic work of early computer visual culture in general—one that adorned the walls of the world’s few computer centers, ultimately placing Mona alongside Snoopy and his pals as the viral images of early computing.

H. P. “Phil” Peterson created Mona by the Numbers amid a wave of cutting-edge research into early computer-controlled image scanners. This line of work proceeded from the epiphany that an analogue image could be discretized into a grid of numeric grayscale values, producing a digital image. Indeed, it was around this time that the word pixel entered the vernacular, in connection with research conducted at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. At the time, Peterson was working on such concerns at the Digigraphic Labs division of Control Data Corporation, one of the major computer companies of the time.

While Peterson was one of a cadre of researchers using early scanners to produce digital image data, it was his invention of a special custom font that would enable the rendering of digital images—and, in turn, the creation of one of the great works of computer art.

The glyphs in Peterson’s font represent the numbers 0–99, each of which is made slightly denser (in terms of the amount of ink coverage) than its predecessor. So, for example, from a slight distance the glyph ‘55’ appears considerably darker than ‘45’, which in turns appears considerably darker than ‘35’, and so forth. With his custom font in hand, Peterson wrote a program that would drive a Control Data Model 280 Digigraphic Scanner to produce grayscale values between 0-99 for the tiny cells of a square-inch photographic slide of the original Mona Lisa.

Next, Peterson developed a CDC 3200 program to drive a Calcomp Model 564 plotter to draw a digital reformulation of Davinci’s original Mona Lisa. This program (and the plotter) operated over a grid of 256 x 390 cells, each about a tenth of an inch on a side. In each cell, the program referenced the 0-99 grayscale value of the corresponding cell in Davinci’s original, and then instructed the plotter to write that number in the cell, using the corresponding glyph from Peterson’s custom font. Really, the word 'font' doesn't do justice, given that writing a single digit entailed over sixty plotter steps!

In total, the work took sixteen hours—and sixteen million plotter steps—to plot. From this plotter drawing, prints were created using a diazo machine, and each print took about fourteen hours to produce! These prints were distributed to computer centers and other Control Data clients as a form of promotion showing the wildly new capabilities of the electronic computer and its accessories, such as image scanners and plotters.

Relative to its source work, Mona by the Numbers is remarkably accurate from even a small distance—and digital in the sense that it transduces the analogue signal of the source photographic slide into a series of discrete symbols, those being the glyphs in Peterson’s custom font. In fact, Peterson playfully situated his piece as “a ‘pure’ digital work of art” in opposition to the “insidious tendency” toward analogue forms that typified what little computer art had been produced to this point. Of course, ‘digital’ here is something of a pun, given that the image is composed of a series of digits.

Mona by the Numbers is among the earliest artworks created on a general-purpose electronic digital computer. While it served a practical marketing purpose, Mona by the Numbers was also closely associated with the nascent form of computer art. It appeared on the cover of the December 1965 issue of Computers and Automation, home of the annual Computer Art Contest that was first held in 1963, and it was discussed in Herbert W. Franke’s touchstone Computergraphik – Computerkunst (1971). A follow-up piece created by Peterson using the same technique, but applied to a photo of Norbert Wiener, was featured in the landmark Cybernetic Serendipity (1968) exhibition.

Most pertinently, it became the seminal work of early computer visual culture, one that worked to canonize the Mona Lisa as a viral image in the nascent culture surrounding the first ASCII art hobbyists who tinkered with line printers driven by mainframe computers.

One quirk of the diazo process is that a print will fade rapidly (in a number of days or months) if exposed to sunlight or even to fluorescent lighting. Moreover, the special diazo paper used for the diazo process is thin and brittle. Ultimately, diazo printing was intended for creating temporary copies, namely of engineering diagrams, as an alternative to the blueprint process. In total, it is not surprising that few prints survived emergence from the dark computer-center rooms where Mona by the Numbers typically hung; the prints that do survive are prone to looking like this. Moreover, as noted above, copies of this work were created by Control Data as promotional giveaways, not bona fide works of art. As such, a given copy likely would have been viewed by its recipient as readily disposable from the get-go, and especially so after it had faded from hanging under the fluorescent lighting favored in the subterranean computer rooms of the day.

We have turned up just two institutional holdings of this piece, one at the Computer History Museum and the other in the fabulous collection of computer art at ZKM. OCLC, Europeana, ArtUK, and ArtCyclopedia do not show any holdings. Individual owners include Andy Patros, who maintains Digital Mona Lisa, a website dedicated to Mona by the Numbers. It appears that no copy is included in the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection. We do not know how many copies were originally created.

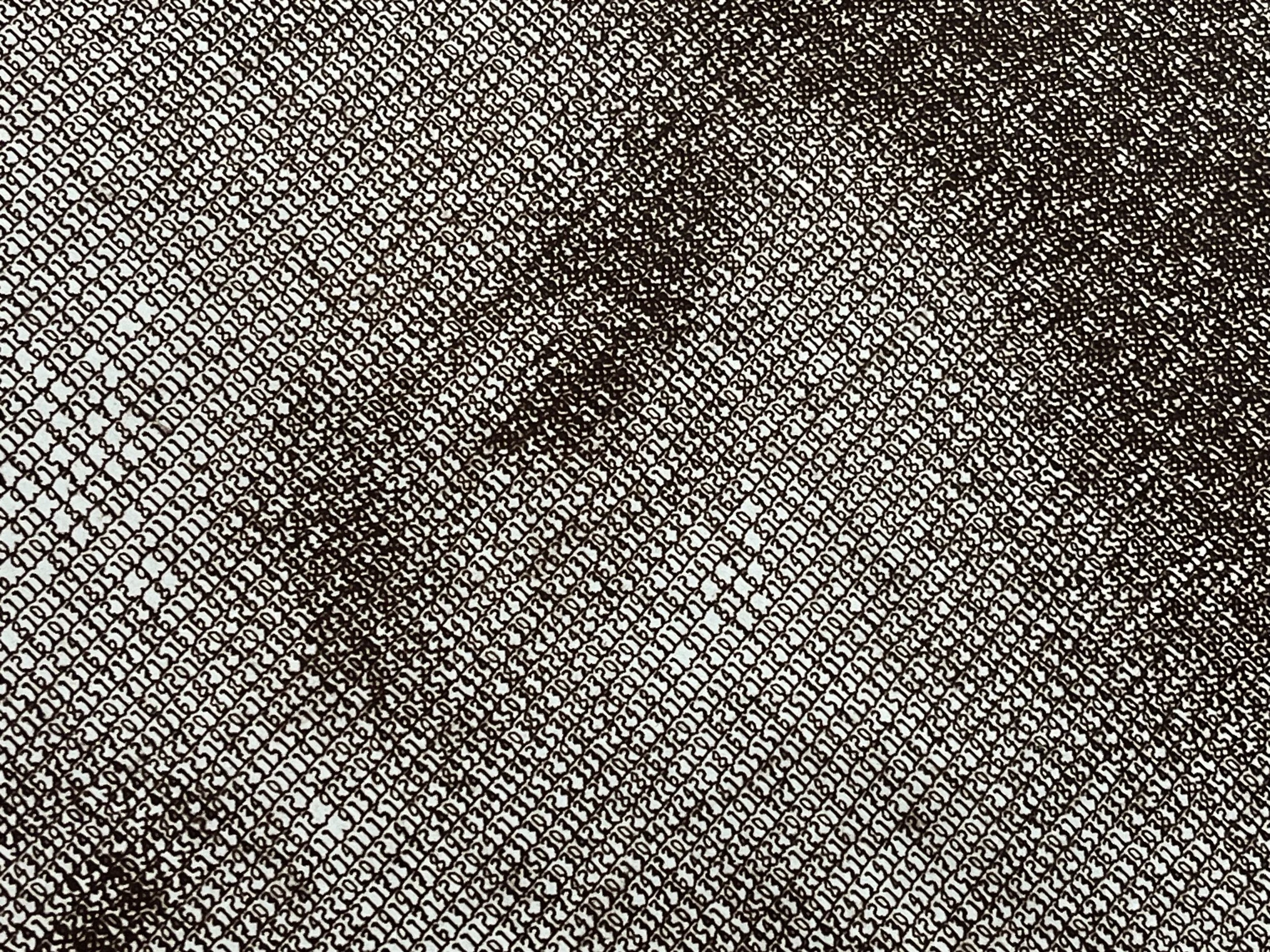

79 x 128 cm. Original diazo sepia print on cream-colored blueline / diazo paper, from a drawing by a CalComp plotter driven by a CDC 3200 computer. The piece is uncut and fully intact, with printed margins indicating the title and artist and his affiliation, along with text along the sides that was printed automatically by the CalComp plotter. What appears to be browning, damage from tape, and holes along the sides are in actuality curious sepia image artifacts that appear to have resulted from a chemical reaction in the diazo paper. Relative to other extant examples, this one shows only minor fading to the image, indicating that it has been shielded from light for its sixty years of existence. This copy appears to have been rolled up for many years, and it is free from creasing. In total, this is an uncut and uncreased copy of a scarce piece, with condition issues in the margins and only minor fading to the image itself.

Among the earliest works of computer art, Mona by the Numbers (1965) was easily the most famous in its own time. Indeed, this masterpiece is arguably the iconic work of early computer visual culture in general—one that adorned the walls of the world’s few computer centers, ultimately placing Mona alongside Snoopy and his pals as the viral images of early computing.

H. P. “Phil” Peterson created Mona by the Numbers amid a wave of cutting-edge research into early computer-controlled image scanners. This line of work proceeded from the epiphany that an analogue image could be discretized into a grid of numeric grayscale values, producing a digital image. Indeed, it was around this time that the word pixel entered the vernacular, in connection with research conducted at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. At the time, Peterson was working on such concerns at the Digigraphic Labs division of Control Data Corporation, one of the major computer companies of the time.

While Peterson was one of a cadre of researchers using early scanners to produce digital image data, it was his invention of a special custom font that would enable the rendering of digital images—and, in turn, the creation of one of the great works of computer art.

The glyphs in Peterson’s font represent the numbers 0–99, each of which is made slightly denser (in terms of the amount of ink coverage) than its predecessor. So, for example, from a slight distance the glyph ‘55’ appears considerably darker than ‘45’, which in turns appears considerably darker than ‘35’, and so forth. With his custom font in hand, Peterson wrote a program that would drive a Control Data Model 280 Digigraphic Scanner to produce grayscale values between 0-99 for the tiny cells of a square-inch photographic slide of the original Mona Lisa.

Next, Peterson developed a CDC 3200 program to drive a Calcomp Model 564 plotter to draw a digital reformulation of Davinci’s original Mona Lisa. This program (and the plotter) operated over a grid of 256 x 390 cells, each about a tenth of an inch on a side. In each cell, the program referenced the 0-99 grayscale value of the corresponding cell in Davinci’s original, and then instructed the plotter to write that number in the cell, using the corresponding glyph from Peterson’s custom font. Really, the word 'font' doesn't do justice, given that writing a single digit entailed over sixty plotter steps!

In total, the work took sixteen hours—and sixteen million plotter steps—to plot. From this plotter drawing, prints were created using a diazo machine, and each print took about fourteen hours to produce! These prints were distributed to computer centers and other Control Data clients as a form of promotion showing the wildly new capabilities of the electronic computer and its accessories, such as image scanners and plotters.

Relative to its source work, Mona by the Numbers is remarkably accurate from even a small distance—and digital in the sense that it transduces the analogue signal of the source photographic slide into a series of discrete symbols, those being the glyphs in Peterson’s custom font. In fact, Peterson playfully situated his piece as “a ‘pure’ digital work of art” in opposition to the “insidious tendency” toward analogue forms that typified what little computer art had been produced to this point. Of course, ‘digital’ here is something of a pun, given that the image is composed of a series of digits.

Mona by the Numbers is among the earliest artworks created on a general-purpose electronic digital computer. While it served a practical marketing purpose, Mona by the Numbers was also closely associated with the nascent form of computer art. It appeared on the cover of the December 1965 issue of Computers and Automation, home of the annual Computer Art Contest that was first held in 1963, and it was discussed in Herbert W. Franke’s touchstone Computergraphik – Computerkunst (1971). A follow-up piece created by Peterson using the same technique, but applied to a photo of Norbert Wiener, was featured in the landmark Cybernetic Serendipity (1968) exhibition.

Most pertinently, it became the seminal work of early computer visual culture, one that worked to canonize the Mona Lisa as a viral image in the nascent culture surrounding the first ASCII art hobbyists who tinkered with line printers driven by mainframe computers.

One quirk of the diazo process is that a print will fade rapidly (in a number of days or months) if exposed to sunlight or even to fluorescent lighting. Moreover, the special diazo paper used for the diazo process is thin and brittle. Ultimately, diazo printing was intended for creating temporary copies, namely of engineering diagrams, as an alternative to the blueprint process. In total, it is not surprising that few prints survived emergence from the dark computer-center rooms where Mona by the Numbers typically hung; the prints that do survive are prone to looking like this. Moreover, as noted above, copies of this work were created by Control Data as promotional giveaways, not bona fide works of art. As such, a given copy likely would have been viewed by its recipient as readily disposable from the get-go, and especially so after it had faded from hanging under the fluorescent lighting favored in the subterranean computer rooms of the day.

We have turned up just two institutional holdings of this piece, one at the Computer History Museum and the other in the fabulous collection of computer art at ZKM. OCLC, Europeana, ArtUK, and ArtCyclopedia do not show any holdings. Individual owners include Andy Patros, who maintains Digital Mona Lisa, a website dedicated to Mona by the Numbers. It appears that no copy is included in the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection. We do not know how many copies were originally created.

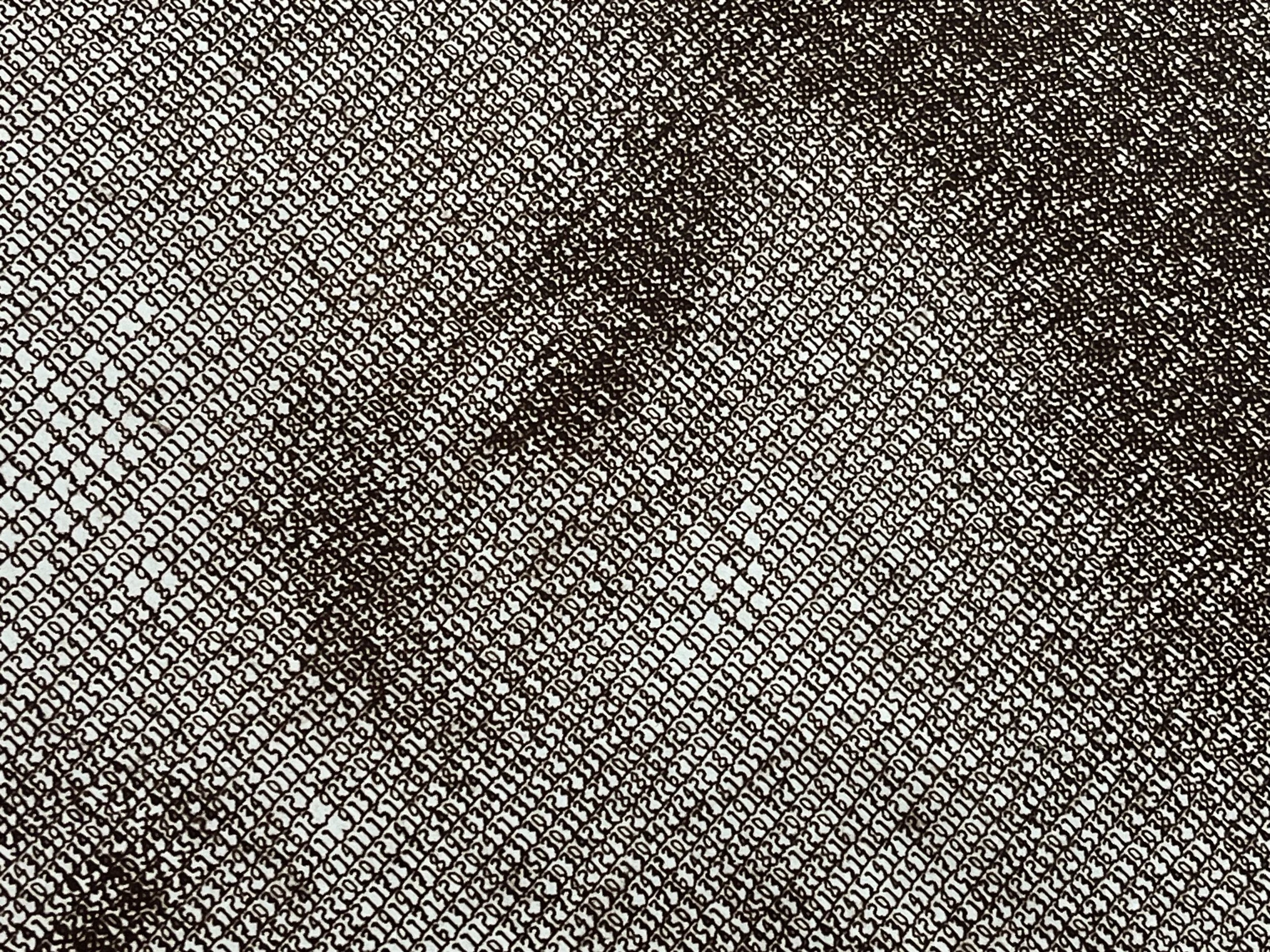

79 x 128 cm. Original diazo sepia print on cream-colored blueline / diazo paper, from a drawing by a CalComp plotter driven by a CDC 3200 computer. The piece is uncut and fully intact, with printed margins indicating the title and artist and his affiliation, along with text along the sides that was printed automatically by the CalComp plotter. What appears to be browning, damage from tape, and holes along the sides are in actuality curious sepia image artifacts that appear to have resulted from a chemical reaction in the diazo paper. Relative to other extant examples, this one shows only minor fading to the image, indicating that it has been shielded from light for its sixty years of existence. This copy appears to have been rolled up for many years, and it is free from creasing. In total, this is an uncut and uncreased copy of a scarce piece, with condition issues in the margins and only minor fading to the image itself.

Among the earliest works of computer art, Mona by the Numbers (1965) was easily the most famous in its own time. Indeed, this masterpiece is arguably the iconic work of early computer visual culture in general—one that adorned the walls of the world’s few computer centers, ultimately placing Mona alongside Snoopy and his pals as the viral images of early computing.

H. P. “Phil” Peterson created Mona by the Numbers amid a wave of cutting-edge research into early computer-controlled image scanners. This line of work proceeded from the epiphany that an analogue image could be discretized into a grid of numeric grayscale values, producing a digital image. Indeed, it was around this time that the word pixel entered the vernacular, in connection with research conducted at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. At the time, Peterson was working on such concerns at the Digigraphic Labs division of Control Data Corporation, one of the major computer companies of the time.

While Peterson was one of a cadre of researchers using early scanners to produce digital image data, it was his invention of a special custom font that would enable the rendering of digital images—and, in turn, the creation of one of the great works of computer art.

The glyphs in Peterson’s font represent the numbers 0–99, each of which is made slightly denser (in terms of the amount of ink coverage) than its predecessor. So, for example, from a slight distance the glyph ‘55’ appears considerably darker than ‘45’, which in turns appears considerably darker than ‘35’, and so forth. With his custom font in hand, Peterson wrote a program that would drive a Control Data Model 280 Digigraphic Scanner to produce grayscale values between 0-99 for the tiny cells of a square-inch photographic slide of the original Mona Lisa.

Next, Peterson developed a CDC 3200 program to drive a Calcomp Model 564 plotter to draw a digital reformulation of Davinci’s original Mona Lisa. This program (and the plotter) operated over a grid of 256 x 390 cells, each about a tenth of an inch on a side. In each cell, the program referenced the 0-99 grayscale value of the corresponding cell in Davinci’s original, and then instructed the plotter to write that number in the cell, using the corresponding glyph from Peterson’s custom font. Really, the word 'font' doesn't do justice, given that writing a single digit entailed over sixty plotter steps!

In total, the work took sixteen hours—and sixteen million plotter steps—to plot. From this plotter drawing, prints were created using a diazo machine, and each print took about fourteen hours to produce! These prints were distributed to computer centers and other Control Data clients as a form of promotion showing the wildly new capabilities of the electronic computer and its accessories, such as image scanners and plotters.

Relative to its source work, Mona by the Numbers is remarkably accurate from even a small distance—and digital in the sense that it transduces the analogue signal of the source photographic slide into a series of discrete symbols, those being the glyphs in Peterson’s custom font. In fact, Peterson playfully situated his piece as “a ‘pure’ digital work of art” in opposition to the “insidious tendency” toward analogue forms that typified what little computer art had been produced to this point. Of course, ‘digital’ here is something of a pun, given that the image is composed of a series of digits.

Mona by the Numbers is among the earliest artworks created on a general-purpose electronic digital computer. While it served a practical marketing purpose, Mona by the Numbers was also closely associated with the nascent form of computer art. It appeared on the cover of the December 1965 issue of Computers and Automation, home of the annual Computer Art Contest that was first held in 1963, and it was discussed in Herbert W. Franke’s touchstone Computergraphik – Computerkunst (1971). A follow-up piece created by Peterson using the same technique, but applied to a photo of Norbert Wiener, was featured in the landmark Cybernetic Serendipity (1968) exhibition.

Most pertinently, it became the seminal work of early computer visual culture, one that worked to canonize the Mona Lisa as a viral image in the nascent culture surrounding the first ASCII art hobbyists who tinkered with line printers driven by mainframe computers.

One quirk of the diazo process is that a print will fade rapidly (in a number of days or months) if exposed to sunlight or even to fluorescent lighting. Moreover, the special diazo paper used for the diazo process is thin and brittle. Ultimately, diazo printing was intended for creating temporary copies, namely of engineering diagrams, as an alternative to the blueprint process. In total, it is not surprising that few prints survived emergence from the dark computer-center rooms where Mona by the Numbers typically hung; the prints that do survive are prone to looking like this. Moreover, as noted above, copies of this work were created by Control Data as promotional giveaways, not bona fide works of art. As such, a given copy likely would have been viewed by its recipient as readily disposable from the get-go, and especially so after it had faded from hanging under the fluorescent lighting favored in the subterranean computer rooms of the day.

We have turned up just two institutional holdings of this piece, one at the Computer History Museum and the other in the fabulous collection of computer art at ZKM. OCLC, Europeana, ArtUK, and ArtCyclopedia do not show any holdings. Individual owners include Andy Patros, who maintains Digital Mona Lisa, a website dedicated to Mona by the Numbers. It appears that no copy is included in the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection. We do not know how many copies were originally created.