Image 1 of 7

Image 1 of 7

Image 2 of 7

Image 2 of 7

Image 3 of 7

Image 3 of 7

Image 4 of 7

Image 4 of 7

Image 5 of 7

Image 5 of 7

Image 6 of 7

Image 6 of 7

Image 7 of 7

Image 7 of 7

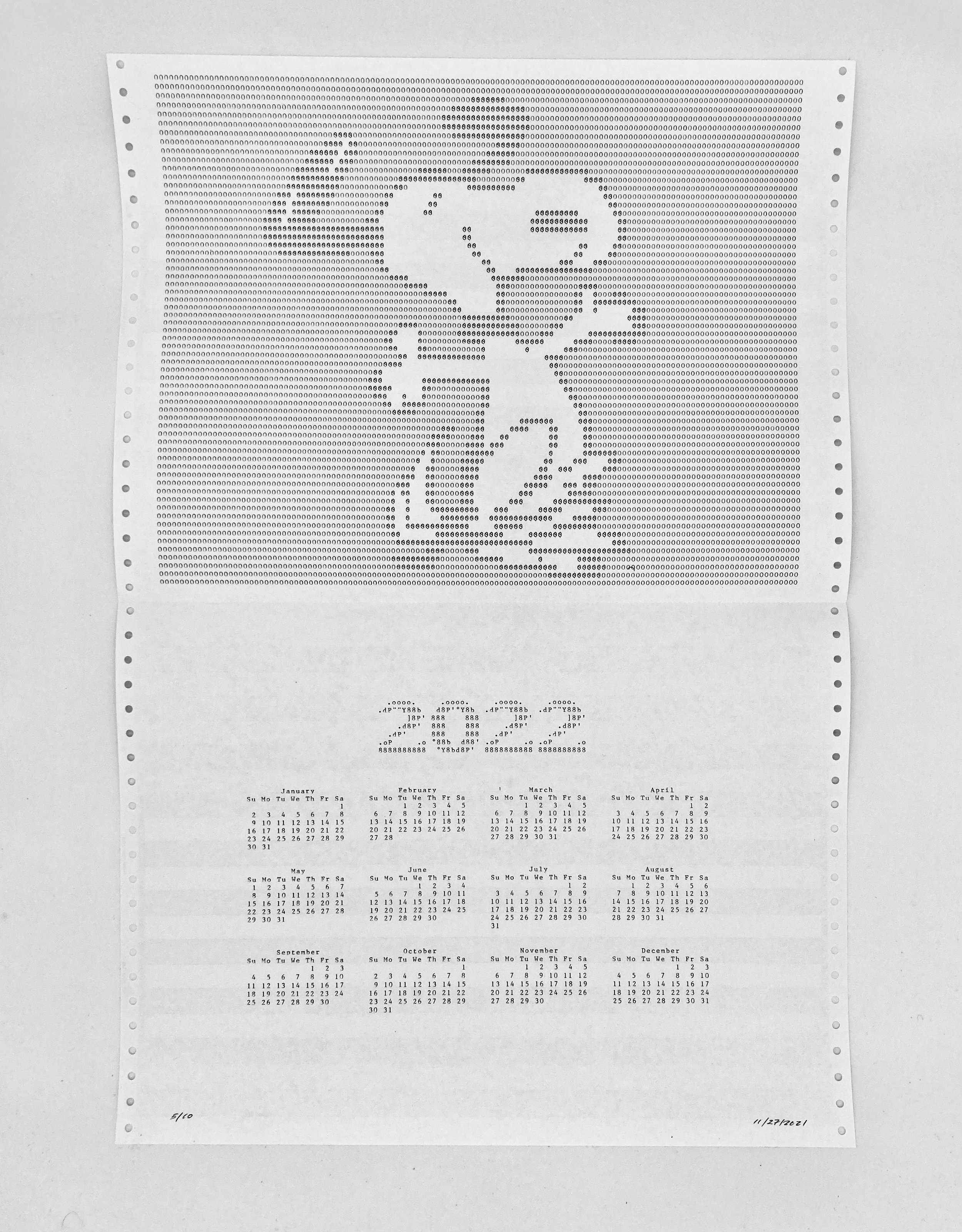

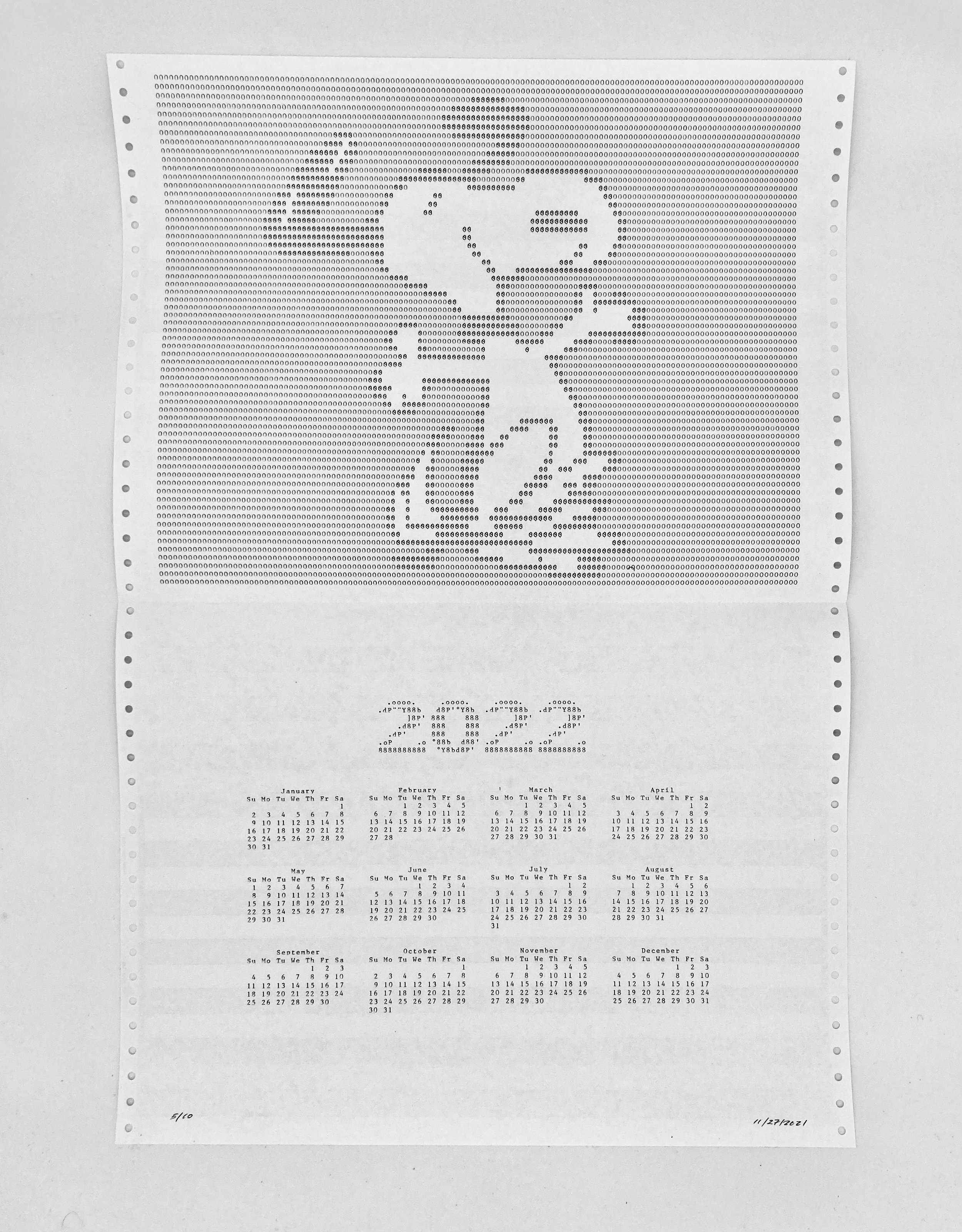

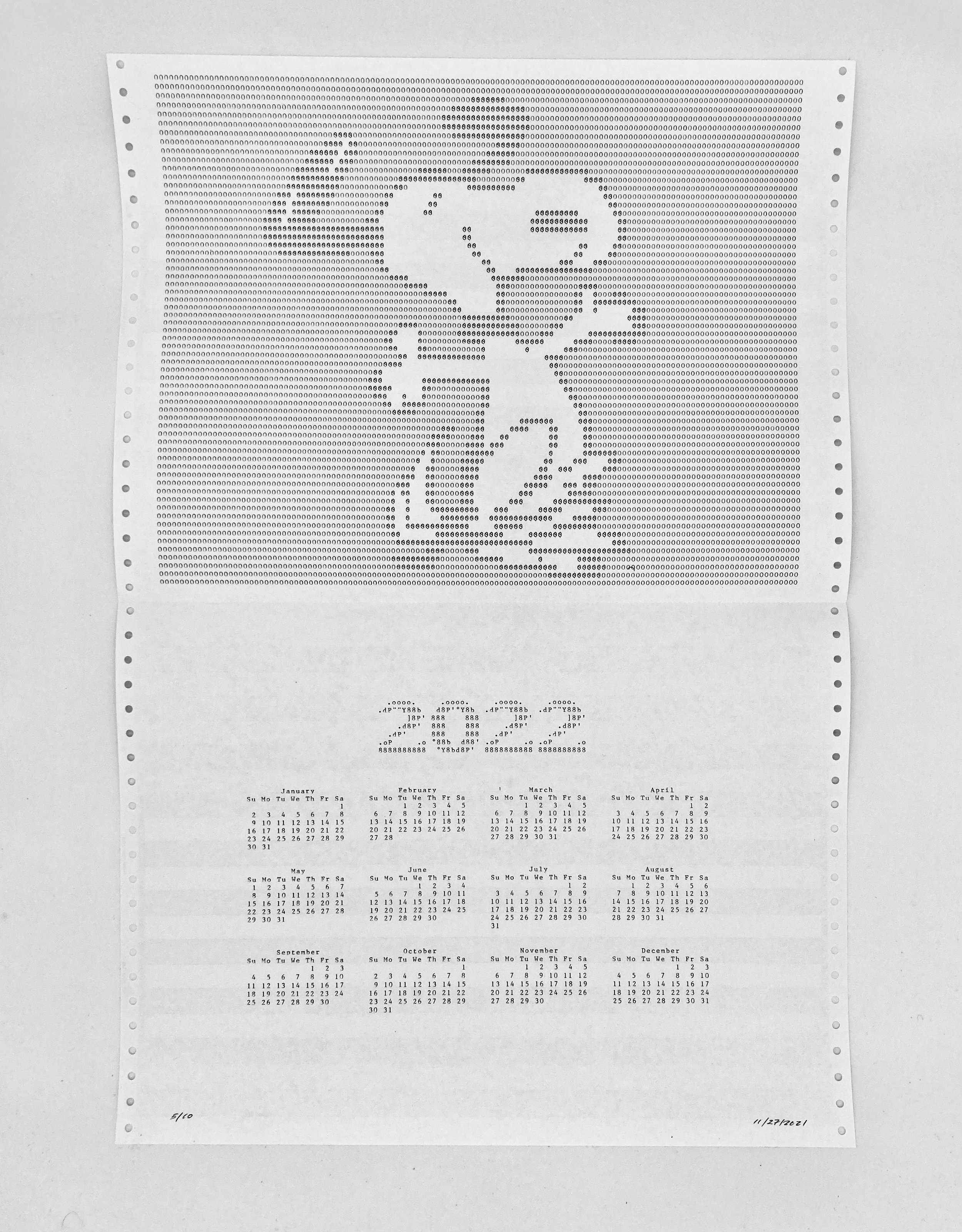

2022 Line-Printer Snoopy Calendar (2021) | Eric Furst

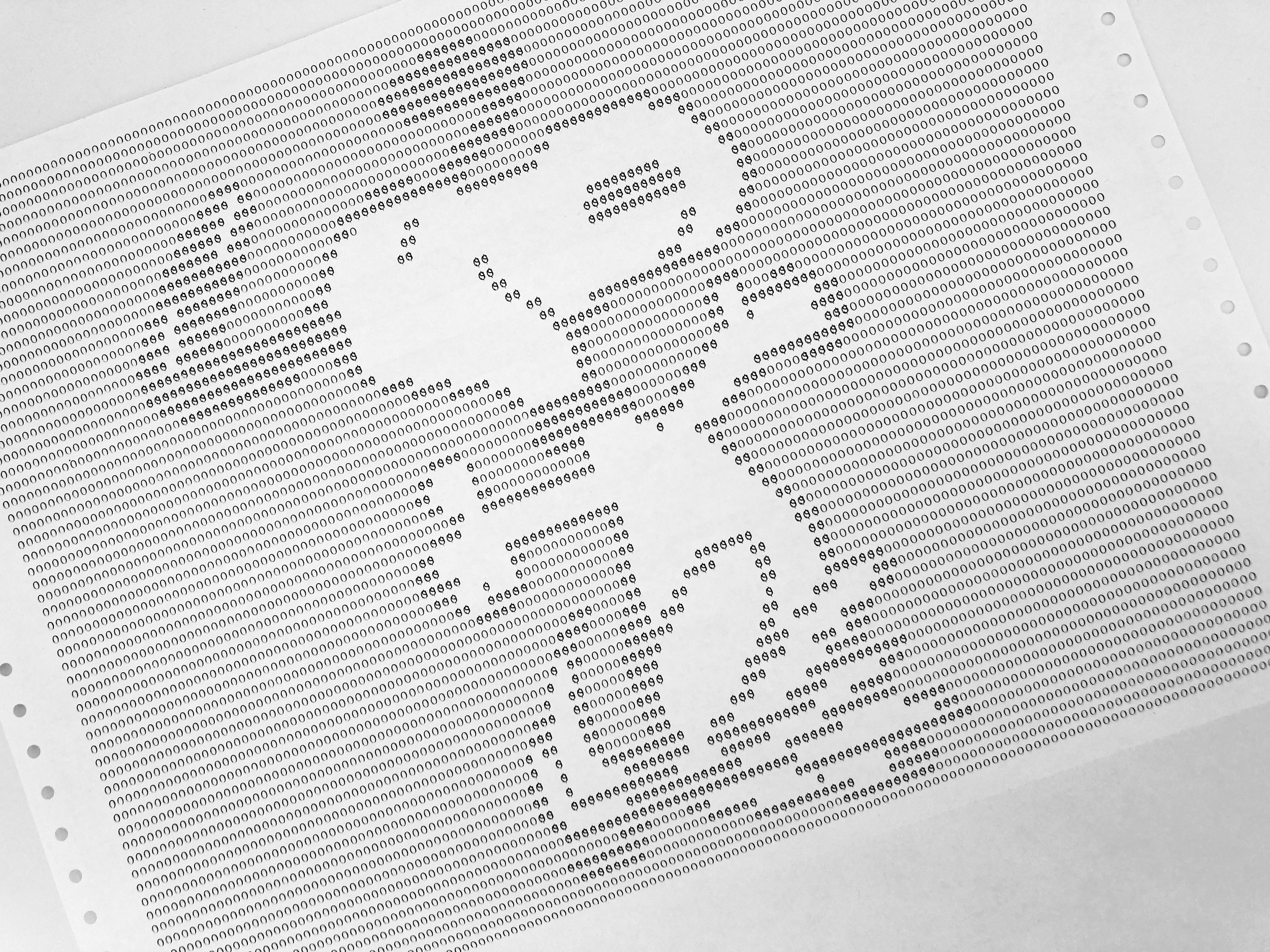

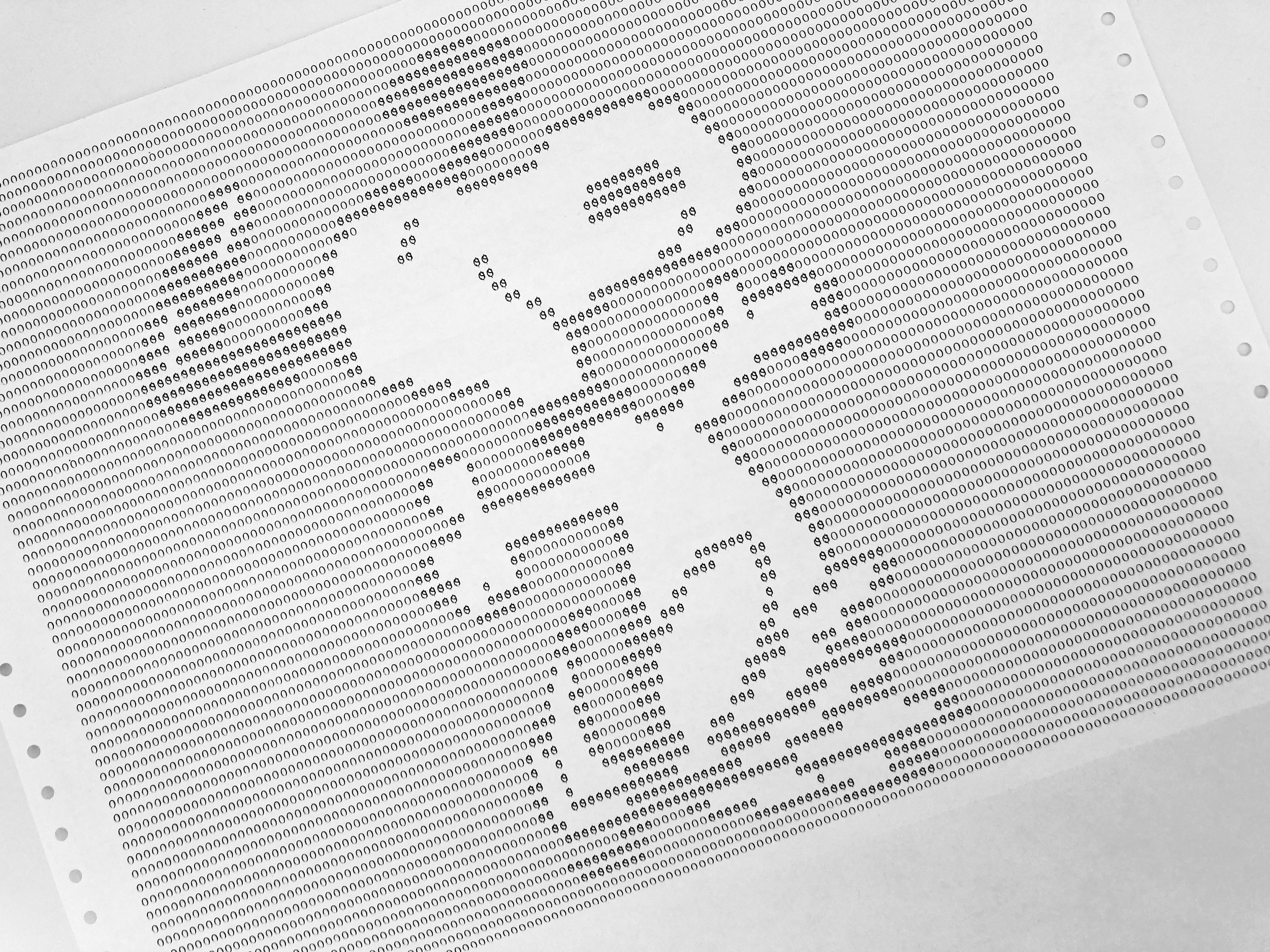

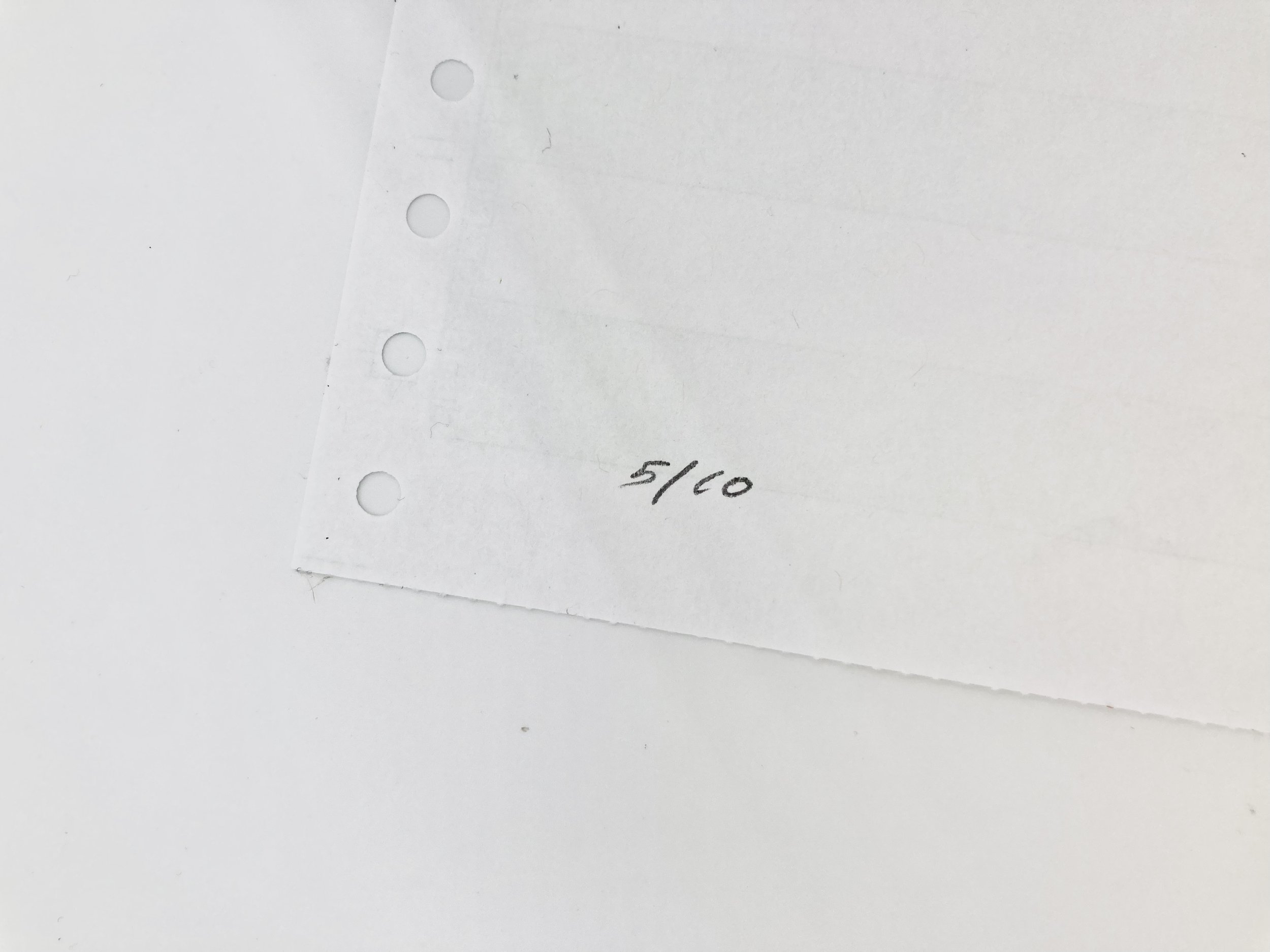

[Philadelphia]: 2021. Line-printer text art on two panels of fanfold tractor-feed computer paper. Printed on a vintage Qume Sprint 11/55, with Courier 10 typewheel, on period green-bar paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb). The content is printed on the reverse only, leaving the green-bar side blank. 38 x 56cm. Creator not attributed. An edition of ten copies, dated and numbered in pencil. As new, distributed on behalf of the creator.

In his legendary satirical piece “Real Programmers Don’t Use PASCAL,” published in the July 1983 issue of Datamation, Ed Post proclaims that “the typical Real Programmer lives in front of a computer terminal,” where “taped to the wall is a line-printer Snoopy calendar for the year 1969.” Not incidentally, the Peanuts characters are strongly associated with early text art on computers, a form whose urtext is arguably the Snoopy calendar.

More dubiously, the production of such artifacts was identified in the late 1970s as the canonical example of “computer crime,” due to a strong association with the unauthorized use of such equipment. In the days before personal computers, computer time was a valuable commodity that was closely monitored by the institutions who owned such machines—and the most rampant form of “computer abuse” was believed to be the creation of line-printer Snoopy calendars. Among those who deemed the practice too innocuous to be criminal was a certain senator from Delaware, who once implored a Department of Justice official to abstain from prosecuting a person accused of producing an example:

BIDEN: Let us level with the public. Let us acknowledge to them, by implication at least, that we are not going to prosecute that particular person. […]

FINNEY (Department of Justice): The Snoopy [calendar] was our case.

BIDEN: Yes. Acknowledge that we are not going to prosecute Snoopy and do not leave the possibility of abuse, which does exist now.

The line-printer Snoopy calendar materializes an impishly radical approach to computing: it is approachable and unsophisticated, results from a freely distributed program (perhaps the most shared early shareware), flouts old-media notions of intellectual property, and prefigures the (once-criminalized) frivolous uses of computing machinery that structure everyday life in the 21st century.

Offered here is a small edition of contemporary examples created by Eric Furst, a Philadelphia-based practitioner in creative computing and conservation whose work deeply engages with vintage hardware and software. His projects in this style include conceptual and visual art punched on paper tape, a port to modern machines of the pioneering Art1 (1968) system for computer art, and other efforts in preservation.

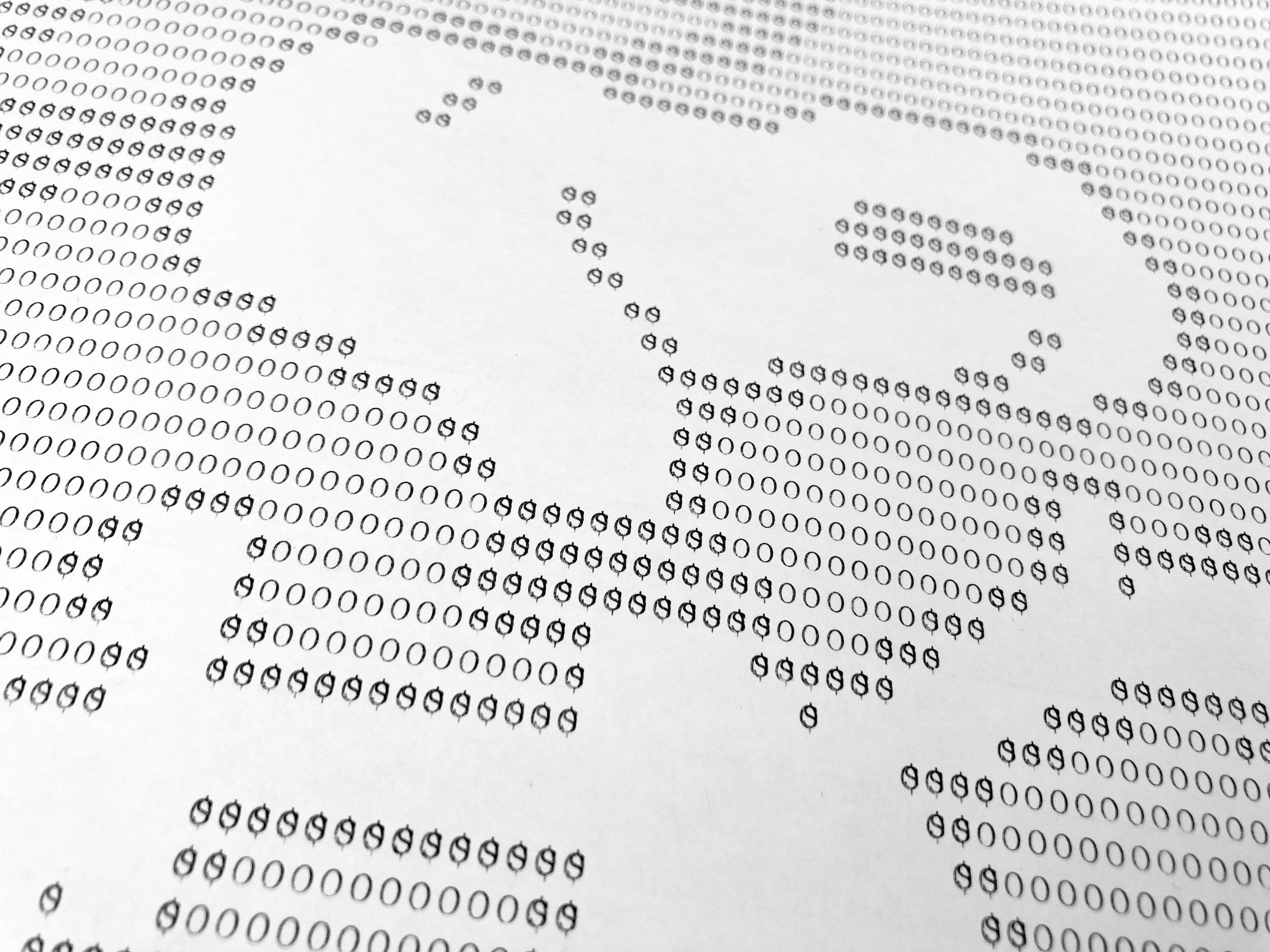

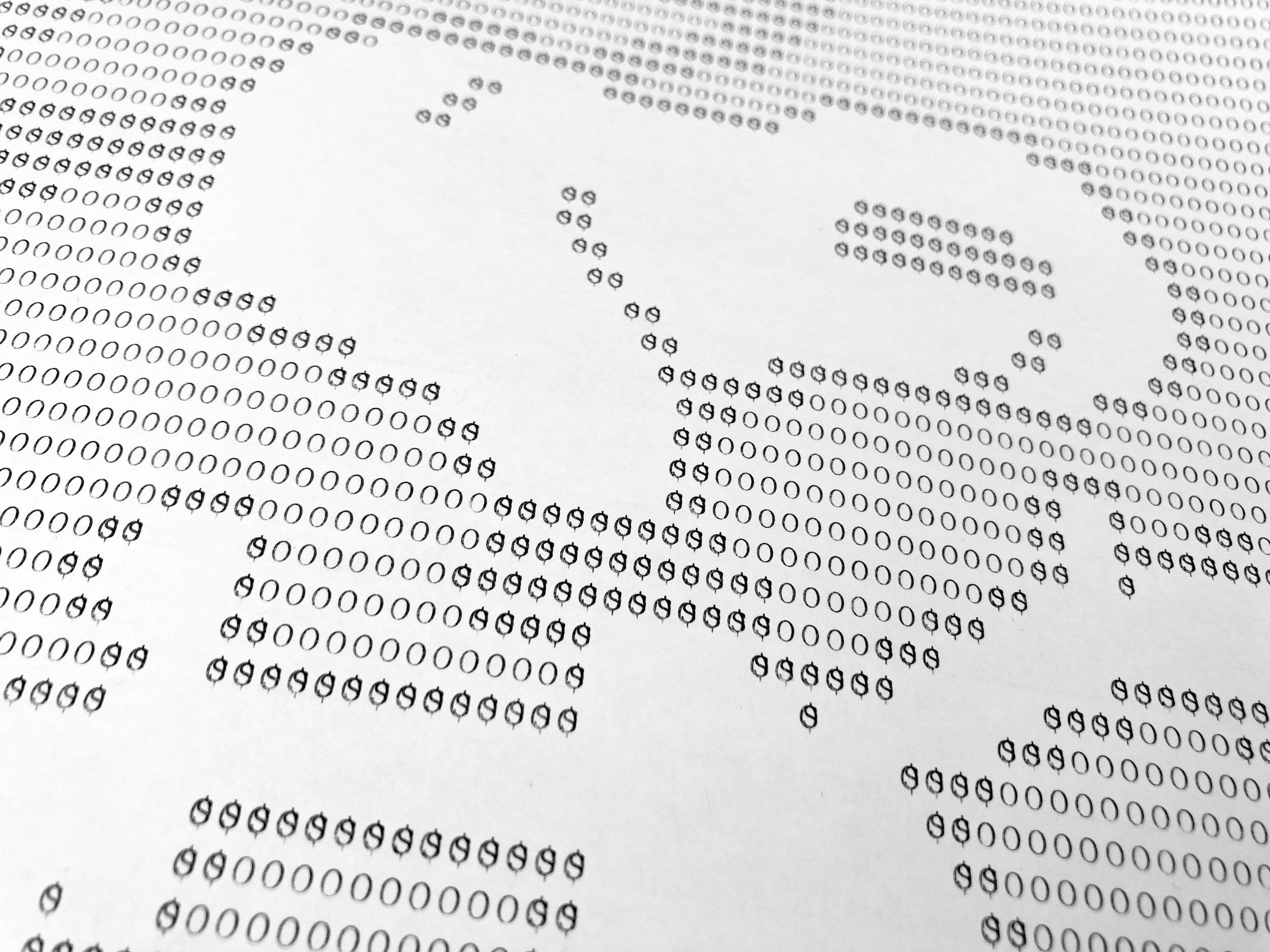

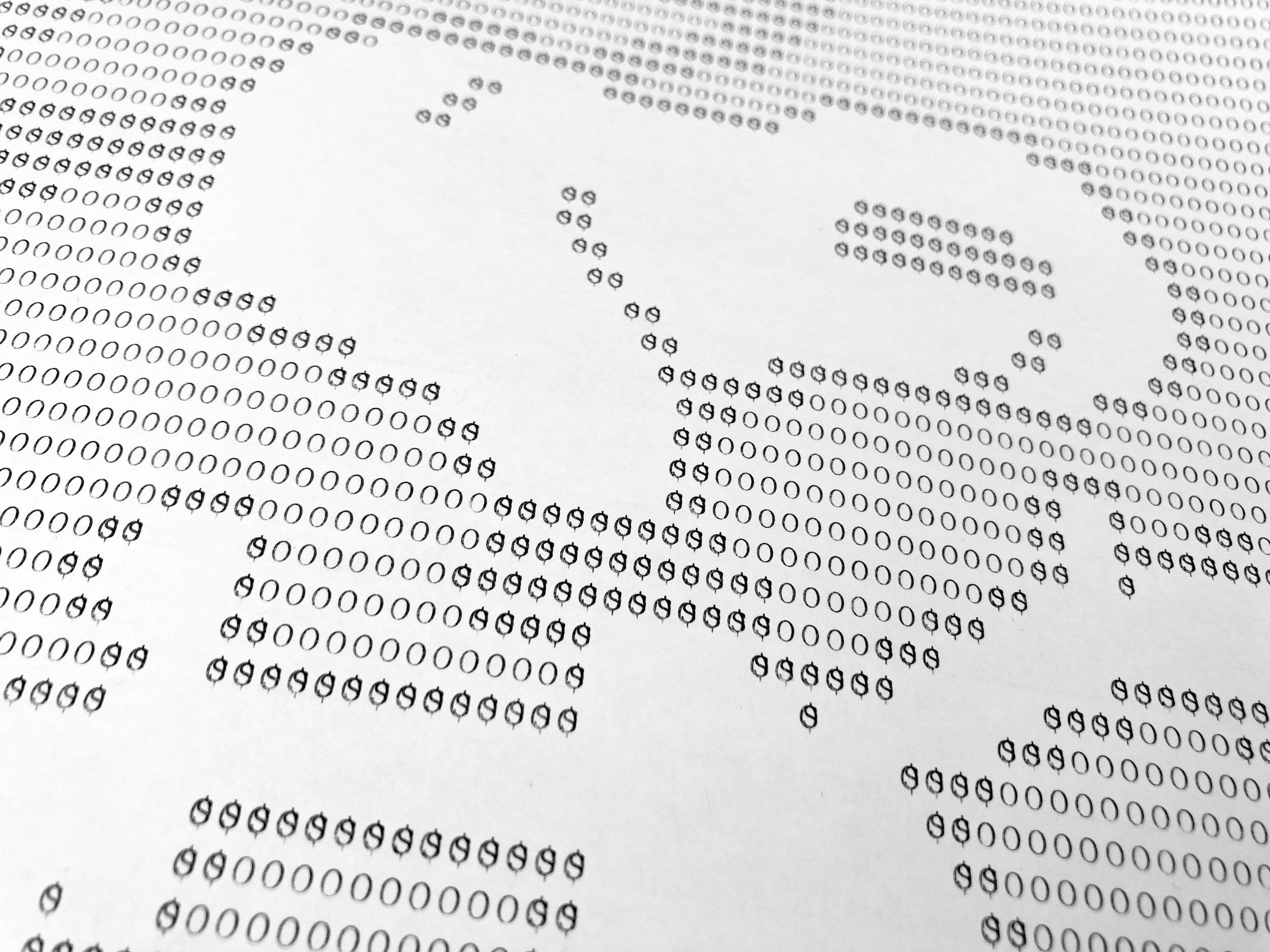

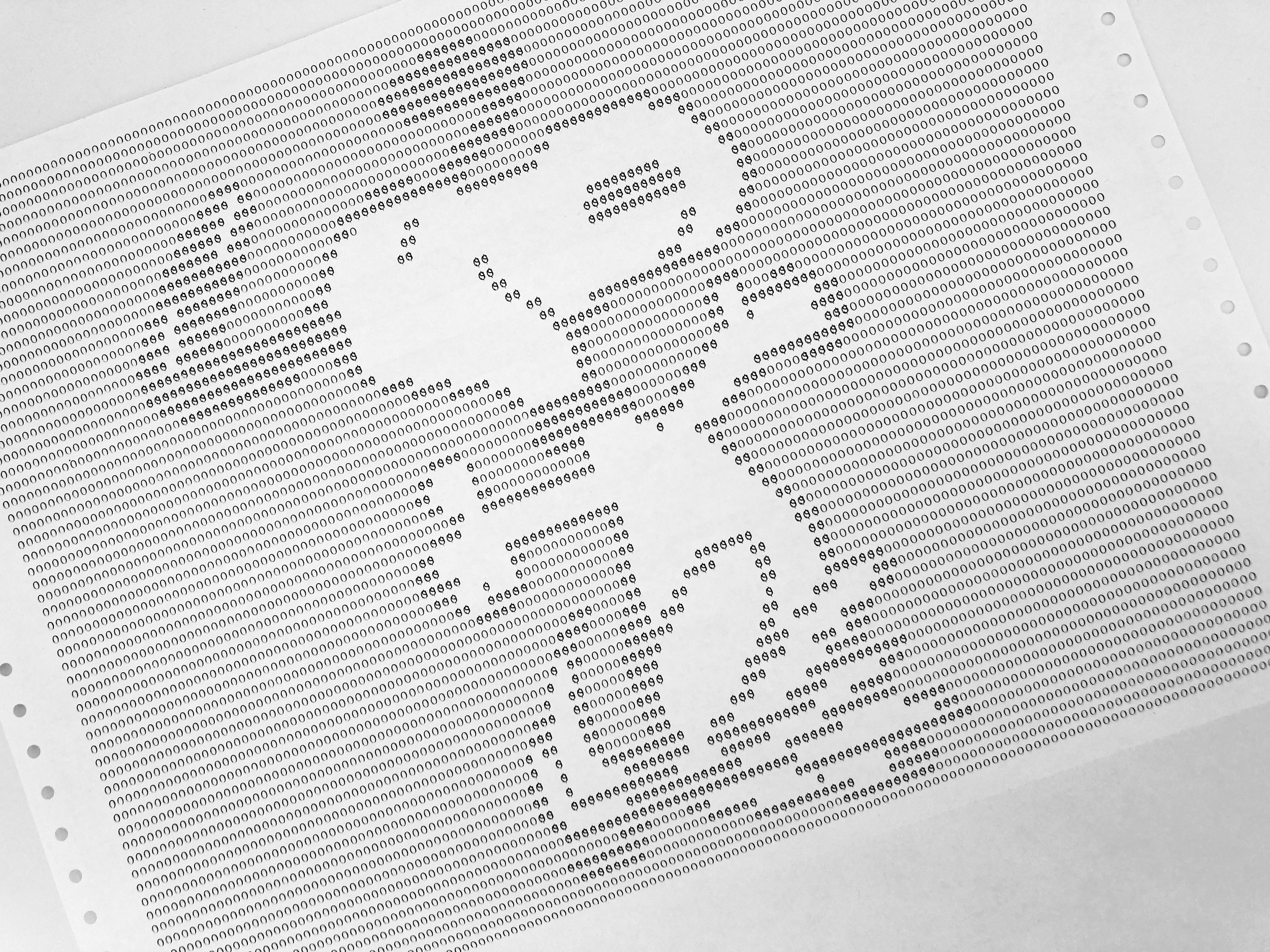

For this project, Furst sought to produce a single-page line-printer Snoopy calendar resembling extant historical examples, such as the 1973 calendar that we recently handled. As he explains in a project write-up, Furst began by experimenting with the famous SNPCAL Fortran shareware program (ca. 1960s), which generates full-page calendars for a user-supplied month. From the source, Furst identified a text image of an exuberant Snoopy—one that makes use of overprinting—and isolated it for use in a single-page year calendar. To produce the actual calendar elements, Furst employed the classic command-line utilities cal (1971) and FIGlet (1991).

Just as the content of this piece was produced using period software, it was in turn physically realized by vintage hardware printing on vintage paper. Specifically, Furst used a Qume Sprint 11/55 printer, outfitted with a Courier 10 typewheel, and printed on green-bar fanfold computer paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb, 14-7/8” x 11”, Perforated) at six lines per inch.

In total, Furst has produced a deeply considered contemporary realization of one of the iconic aesthetic artifacts of hacker culture. This radical material relic of early computing is an enduring folk piece that, clearly, still enchants practitioners today.

Aleator Press is pleased to offer examples from a lovingly crafted edition of ten copies, each numbered and dated in pencil by Furst. We are selling these on his behalf, just in time for the new year.

The perfect gift for the Real Programmer—or computer criminal—in your life.

[Philadelphia]: 2021. Line-printer text art on two panels of fanfold tractor-feed computer paper. Printed on a vintage Qume Sprint 11/55, with Courier 10 typewheel, on period green-bar paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb). The content is printed on the reverse only, leaving the green-bar side blank. 38 x 56cm. Creator not attributed. An edition of ten copies, dated and numbered in pencil. As new, distributed on behalf of the creator.

In his legendary satirical piece “Real Programmers Don’t Use PASCAL,” published in the July 1983 issue of Datamation, Ed Post proclaims that “the typical Real Programmer lives in front of a computer terminal,” where “taped to the wall is a line-printer Snoopy calendar for the year 1969.” Not incidentally, the Peanuts characters are strongly associated with early text art on computers, a form whose urtext is arguably the Snoopy calendar.

More dubiously, the production of such artifacts was identified in the late 1970s as the canonical example of “computer crime,” due to a strong association with the unauthorized use of such equipment. In the days before personal computers, computer time was a valuable commodity that was closely monitored by the institutions who owned such machines—and the most rampant form of “computer abuse” was believed to be the creation of line-printer Snoopy calendars. Among those who deemed the practice too innocuous to be criminal was a certain senator from Delaware, who once implored a Department of Justice official to abstain from prosecuting a person accused of producing an example:

BIDEN: Let us level with the public. Let us acknowledge to them, by implication at least, that we are not going to prosecute that particular person. […]

FINNEY (Department of Justice): The Snoopy [calendar] was our case.

BIDEN: Yes. Acknowledge that we are not going to prosecute Snoopy and do not leave the possibility of abuse, which does exist now.

The line-printer Snoopy calendar materializes an impishly radical approach to computing: it is approachable and unsophisticated, results from a freely distributed program (perhaps the most shared early shareware), flouts old-media notions of intellectual property, and prefigures the (once-criminalized) frivolous uses of computing machinery that structure everyday life in the 21st century.

Offered here is a small edition of contemporary examples created by Eric Furst, a Philadelphia-based practitioner in creative computing and conservation whose work deeply engages with vintage hardware and software. His projects in this style include conceptual and visual art punched on paper tape, a port to modern machines of the pioneering Art1 (1968) system for computer art, and other efforts in preservation.

For this project, Furst sought to produce a single-page line-printer Snoopy calendar resembling extant historical examples, such as the 1973 calendar that we recently handled. As he explains in a project write-up, Furst began by experimenting with the famous SNPCAL Fortran shareware program (ca. 1960s), which generates full-page calendars for a user-supplied month. From the source, Furst identified a text image of an exuberant Snoopy—one that makes use of overprinting—and isolated it for use in a single-page year calendar. To produce the actual calendar elements, Furst employed the classic command-line utilities cal (1971) and FIGlet (1991).

Just as the content of this piece was produced using period software, it was in turn physically realized by vintage hardware printing on vintage paper. Specifically, Furst used a Qume Sprint 11/55 printer, outfitted with a Courier 10 typewheel, and printed on green-bar fanfold computer paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb, 14-7/8” x 11”, Perforated) at six lines per inch.

In total, Furst has produced a deeply considered contemporary realization of one of the iconic aesthetic artifacts of hacker culture. This radical material relic of early computing is an enduring folk piece that, clearly, still enchants practitioners today.

Aleator Press is pleased to offer examples from a lovingly crafted edition of ten copies, each numbered and dated in pencil by Furst. We are selling these on his behalf, just in time for the new year.

The perfect gift for the Real Programmer—or computer criminal—in your life.

[Philadelphia]: 2021. Line-printer text art on two panels of fanfold tractor-feed computer paper. Printed on a vintage Qume Sprint 11/55, with Courier 10 typewheel, on period green-bar paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb). The content is printed on the reverse only, leaving the green-bar side blank. 38 x 56cm. Creator not attributed. An edition of ten copies, dated and numbered in pencil. As new, distributed on behalf of the creator.

In his legendary satirical piece “Real Programmers Don’t Use PASCAL,” published in the July 1983 issue of Datamation, Ed Post proclaims that “the typical Real Programmer lives in front of a computer terminal,” where “taped to the wall is a line-printer Snoopy calendar for the year 1969.” Not incidentally, the Peanuts characters are strongly associated with early text art on computers, a form whose urtext is arguably the Snoopy calendar.

More dubiously, the production of such artifacts was identified in the late 1970s as the canonical example of “computer crime,” due to a strong association with the unauthorized use of such equipment. In the days before personal computers, computer time was a valuable commodity that was closely monitored by the institutions who owned such machines—and the most rampant form of “computer abuse” was believed to be the creation of line-printer Snoopy calendars. Among those who deemed the practice too innocuous to be criminal was a certain senator from Delaware, who once implored a Department of Justice official to abstain from prosecuting a person accused of producing an example:

BIDEN: Let us level with the public. Let us acknowledge to them, by implication at least, that we are not going to prosecute that particular person. […]

FINNEY (Department of Justice): The Snoopy [calendar] was our case.

BIDEN: Yes. Acknowledge that we are not going to prosecute Snoopy and do not leave the possibility of abuse, which does exist now.

The line-printer Snoopy calendar materializes an impishly radical approach to computing: it is approachable and unsophisticated, results from a freely distributed program (perhaps the most shared early shareware), flouts old-media notions of intellectual property, and prefigures the (once-criminalized) frivolous uses of computing machinery that structure everyday life in the 21st century.

Offered here is a small edition of contemporary examples created by Eric Furst, a Philadelphia-based practitioner in creative computing and conservation whose work deeply engages with vintage hardware and software. His projects in this style include conceptual and visual art punched on paper tape, a port to modern machines of the pioneering Art1 (1968) system for computer art, and other efforts in preservation.

For this project, Furst sought to produce a single-page line-printer Snoopy calendar resembling extant historical examples, such as the 1973 calendar that we recently handled. As he explains in a project write-up, Furst began by experimenting with the famous SNPCAL Fortran shareware program (ca. 1960s), which generates full-page calendars for a user-supplied month. From the source, Furst identified a text image of an exuberant Snoopy—one that makes use of overprinting—and isolated it for use in a single-page year calendar. To produce the actual calendar elements, Furst employed the classic command-line utilities cal (1971) and FIGlet (1991).

Just as the content of this piece was produced using period software, it was in turn physically realized by vintage hardware printing on vintage paper. Specifically, Furst used a Qume Sprint 11/55 printer, outfitted with a Courier 10 typewheel, and printed on green-bar fanfold computer paper (new old stock, Universal UNV15852 Computer Paper, 20lb, 14-7/8” x 11”, Perforated) at six lines per inch.

In total, Furst has produced a deeply considered contemporary realization of one of the iconic aesthetic artifacts of hacker culture. This radical material relic of early computing is an enduring folk piece that, clearly, still enchants practitioners today.

Aleator Press is pleased to offer examples from a lovingly crafted edition of ten copies, each numbered and dated in pencil by Furst. We are selling these on his behalf, just in time for the new year.

The perfect gift for the Real Programmer—or computer criminal—in your life.